Little work has been done to understand young people’s willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines. Above: a COVID-19 vaccination clinic at the University of Toronto Mississauga campus on May 6. THE CANADIAN PRESS/ Tijana Martin

Tracie O. Afifi, University of Manitoba; Ashley Stewart-Tufescu, University of Manitoba; Janique Fortier, University of Manitoba; Samantha Salmon, University of Manitoba; S. Michelle Driedger, University of Manitoba, and Tamara Taillieu, University of Manitoba

Ending the coronavirus pandemic rests partly on a large uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, with the goal of reaching herd immunity. Recently in Canada, the age for vaccine eligibility has been decreasing to include young adults and adolescents. However, little work has been done to understand willingness to receive the vaccine among this age group.

Our group from the Childhood Adversity and Resilience (CARe) Research Team at University of Manitoba recently published a new study aimed at understanding the COVID-19 vaccine intentions of older adolescents and young adults, and reasons for any expressed vaccine hesitancy.

Our participants included 664 young people aged 16 to 21 years from Manitoba. We also examined how sociodemographic factors, existing health problems, COVID-19 knowledge and childhood adversity history might be related to vaccine intention.

Understanding these risk factors is important because we also know that social inequities are associated with vulnerability to COVID-19. Communities and individuals who have experienced adversity, such as child maltreatment or low socioeconomic status, may have limited access to health care and may be disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Extending knowledge in this area may have important implications for informing public health efforts to slow the transmission of the virus.

Vaccine hesitancy

Historically, there have always been some that are reluctant to receive vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy, which is one of the top 10 threats to global public health, exists on a spectrum. It includes those who delay getting vaccines, only accept some vaccines or refuse all vaccines.

Understanding who might be more likely to be vaccine hesitant and reasons for their reluctance can help inform public health strategies aimed at increasing vaccine uptake. This is critical since herd immunity through vaccination is arguably the only way to end the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evidence on COVID-19 vaccine intention

A sign in Washington, D.C., advertises a free vaccine drive for people ages 12 and over. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

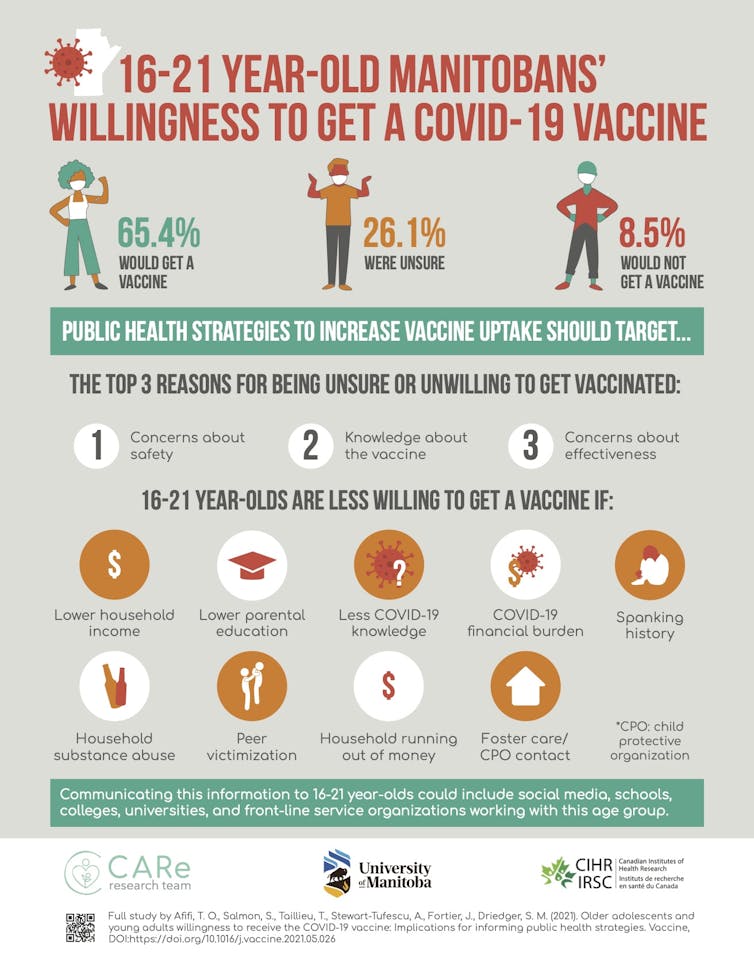

Among our older adolescent and young adult study sample, 65.4 per cent indicated a willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine, 8.5 per cent indicated they would not get a vaccine and 26.1 per cent were unsure. Males and females were equal in their intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.

Those who were less willing to get a vaccine included individuals who had less knowledge about COVID-19 and those who had financial burdens due to COVID-19. Living in a lower-income household or a household that runs out of money or having parents with lower education level were also linked with being less willing to get a vaccine.

Several adverse childhood experiences were also linked to vaccine hesitancy. These included household substance use, a spanking history, a history of being victimized by peers and a history of being in foster care or contact with a child protection organization.

Top 3 reasons for being unsure or unwilling to get a vaccine

The top three reasons for being unsure or unwilling to get a vaccine were:

- Concerns about safety.

- Lack of knowledge about the vaccine.

- Concerns about effectiveness.

We noted sex differences for some reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Males were more likely to indicate not being concerned about getting COVID-19. Females were more likely to report feeling like they did not have enough information about the vaccine on which to make a decision.

Strategies to increase vaccine uptake

Increasing uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among older adolescents and young adults may require appropriately communicating information specifically about vaccine safety, how it works to protect against illness and why it is important to protect oneself and others against a COVID-19 infection.

Some sex-specific messaging may also be useful. Young men need to understand why protecting oneself against infection is important. Young women need more vaccine information for decision-making.

Study findings on vaccine hesitancy in adolescents and young adults. Tracie Afifi, Author provided

Communication messaging could include social media, as well as messaging in schools, colleges and universities. It might also be useful to engage front-line service organizations that work with youth that might serve as possible communication channels for trusted information.

This messaging should not only address the three top reasons stated for vaccine hesitancy, but also try to reach youth who are less likely to be willing to get the vaccine.

Although this research was conducted using a community sample from Manitoba, there is no reason to believe that the findings would be substantively different from other older adolescents and young adults. We recommend that these strategies be considered for broader implementation across Canada and beyond.

It is important to implement strategies to limit the spread of COVID-19 among older adolescents and young adults since this age group may have greater potential to spread COVID-19 due to the nature of some of their jobs, increased likelihood of socialization and reduced adherence to public health guidelines.

Public health strategies that specifically target older adolescents and young adults using these recommendations may be successful in increasing inoculation uptake and play an important role in ending the pandemic.

Tracie O. Afifi, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Childhood Adversity and Resilience, University of Manitoba; Ashley Stewart-Tufescu, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Work, University of Manitoba; Janique Fortier, Research Associate, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba; Samantha Salmon, Research Associate in Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba; S. Michelle Driedger, Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, and Tamara Taillieu, Instructor I and Research Associate, Department of Community Health Sciences, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

« Voix de la SRC » est une série d’interventions écrites assurées par des membres de la Société royale du Canada. Les articles, rédigés par la nouvelle génération du leadership académique du Canada, apportent un regard opportun sur des sujets d’importance pour les Canadiens. Les opinions présentées sont celles des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de la Société royale du Canada.