Migrating monarch butterflies rest at Pismo Beach, Calif. on their way to Mexico. (Shutterstock)

Alana Wilcox, University of Guelph and Ryan Norris, University of Guelph

Each year, thousands of hobbyists and educators across North America collect monarch eggs or caterpillars from the wild to raise indoors and patiently wait for butterflies to emerge. Raising monarch butterflies indoors has become an increasingly popular activity that can have numerous benefits.

Captively reared monarchs provide a unique opportunity for people to learn about the complex life cycle of butterflies and, at the same time, help raise awareness about monarch conservation. However, rearing monarchs (and other butterflies) must be done responsibly and in moderation to make sure that it does not have a negative effect on the population.

Monarch butterflies undergo a multi-generational migration in spring and summer that will bring them as far north as Canada and then, in the fall, a new generation of monarchs undergo a unique transformation that prepares them for a single-bout long-distance migration south. These larger, stronger monarch butterflies will travel more than 4,500 kilometres to congregate and overwinter by the millions in the tree canopies high in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico.

A PBS Nature special on overwintering monarch butterflies in Mexico.

Population decline

The overwintering population of eastern monarch butterflies, however, has been dwindling from an occupancy level of 44.95 hectares in 1997 to 14.95 hectares in 2019 to five hectares this year. Some causes of this decline are thought to be loss of milkweed on which caterpillars feed, long-term changes in climate and deforestation at their overwintering sites. This has caused concern about the likelihood of extinction and the loss of the migratory phenomenon.

Rearing monarchs indoors has been touted as a way to help bolster population numbers and mitigate declines. In reality, indoor rearing probably does little to supplement the wild population, but arguably goes a long way towards awareness and education.

The practice of indoor rearing is not without controversy and has been considered potentially harmful due to the negative impact it could have on butterfly health and the risk it could pose to the butterflies’ ability to migrate to Mexico.

However, our recent research provides some evidence that monarchs raised indoors may still be able to migrate south to their overwintering grounds.

Monarch butterfly with a radio-tracking tag. (Wilcox), Author provided

Disoriented butterflies

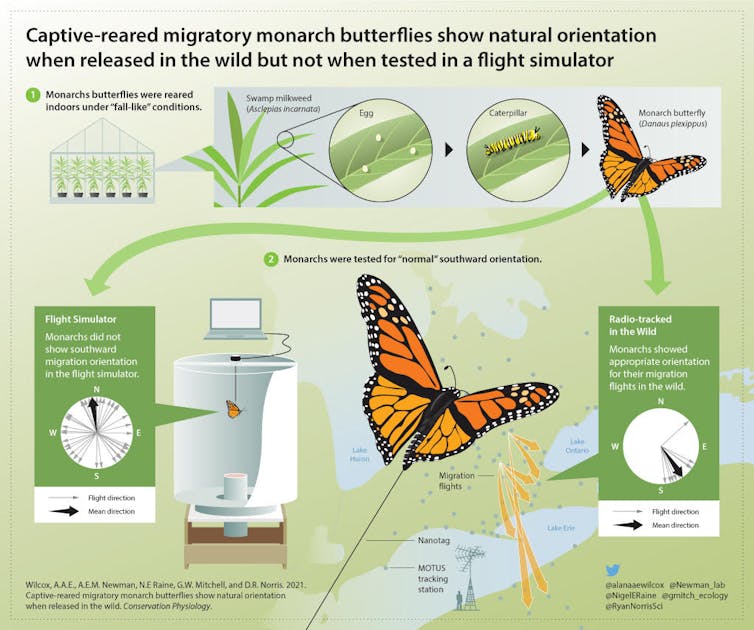

Our team at the University of Guelph raised monarch caterpillars on milkweed indoors in controlled environmental conditions that approximated what monarchs would experience naturally in the wild. Once butterflies emerged from their cocoons, they were tested in a flight simulator, a large open vessel with a digital sensor that recorded which direction the monarchs attempted to fly.

The results from this experiment were consistent with previous research showing that indoor-reared monarchs, on average, did not orient in the proper direction for migration to Mexico.

Monarch butterflies’ inability to orient in the flight simulator could be the result of a lack of exposure to natural and direct sunlight during development. Many animals are equipped with an internal clock that tells the animal when to perform certain activities. For monarch butterflies, this internal clock is located in their antennae and, when coupled with visual information on the sun’s position, tells the monarch which direction it should fly each fall.

Monarch butterflies hatched in captivity but released in the wild were found to join the southward migration. (Wilcox, Newman, Raine, Mitchell, and Norris), Author provided

Recalibration in natural light

Given this, our research team went one step further to determine if indoor-reared monarchs exposed to natural environmental conditions and sunlight after they were released could calibrate their internal compass and fly south.

To do so, our team attached tiny radio transmitters to a second group of indoor-reared monarchs and released the butterflies into the wild. The radio transmitters emit a signal during migration and, if a monarch flies close enough, can be received at one of several hundred automatic radio receiving towers scattered across North America, called the Motus telemetry array.

We detected 29 butterflies at the beginning of migration and found that, given some time outdoors, these butterflies were able to get their bearings and fly southward. This suggests that under certain controlled conditions, raising monarchs indoors may not affect their orientation and ability to start migration.

Indoor rearing offers a valuable tool for learning and fostering a connection to nature. Our results help curb concern that indoor rearing negatively impacts monarch orientation.

While more research needs to be conducted to determine how monarchs perform under different indoor conditions and at different rearing locations in North America, our research suggests that monarch enthusiasts may be able to continue enjoying the wonderful experience of raising these butterflies at home.

Alana Wilcox, Researcher, Conservation biology, University of Guelph and Ryan Norris, Associate Professor, Member of the Royal Society of Canada's College of New Scholars, Artists and Scientists, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

« Voix de la SRC » est une série d’interventions écrites assurées par des membres de la Société royale du Canada. Les articles, rédigés par la nouvelle génération du leadership académique du Canada, apportent un regard opportun sur des sujets d’importance pour les Canadiens. Les opinions présentées sont celles des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de la Société royale du Canada.