Dr. Sonja Boon wears many hats, including adjunct professor in the Department of Gender Studies at Memorial University, mentor in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction at the University of King’s College, and RSC College Member – but above all, she is a storyteller. In this interview, she shares insights into her new edited book, Dear Mr. Smallwood, which explores how everyday Newfoundlanders and Labradorians navigated their country’s entry into Confederation with Canada.

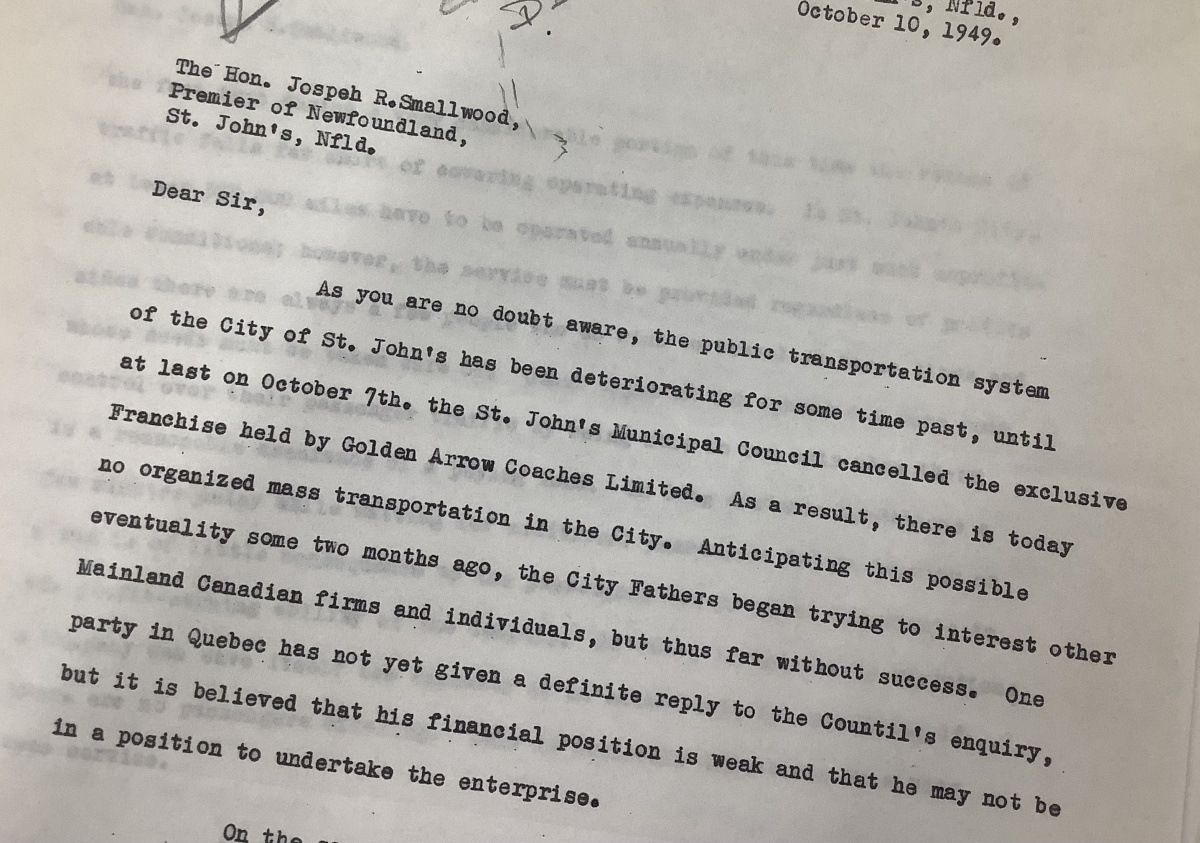

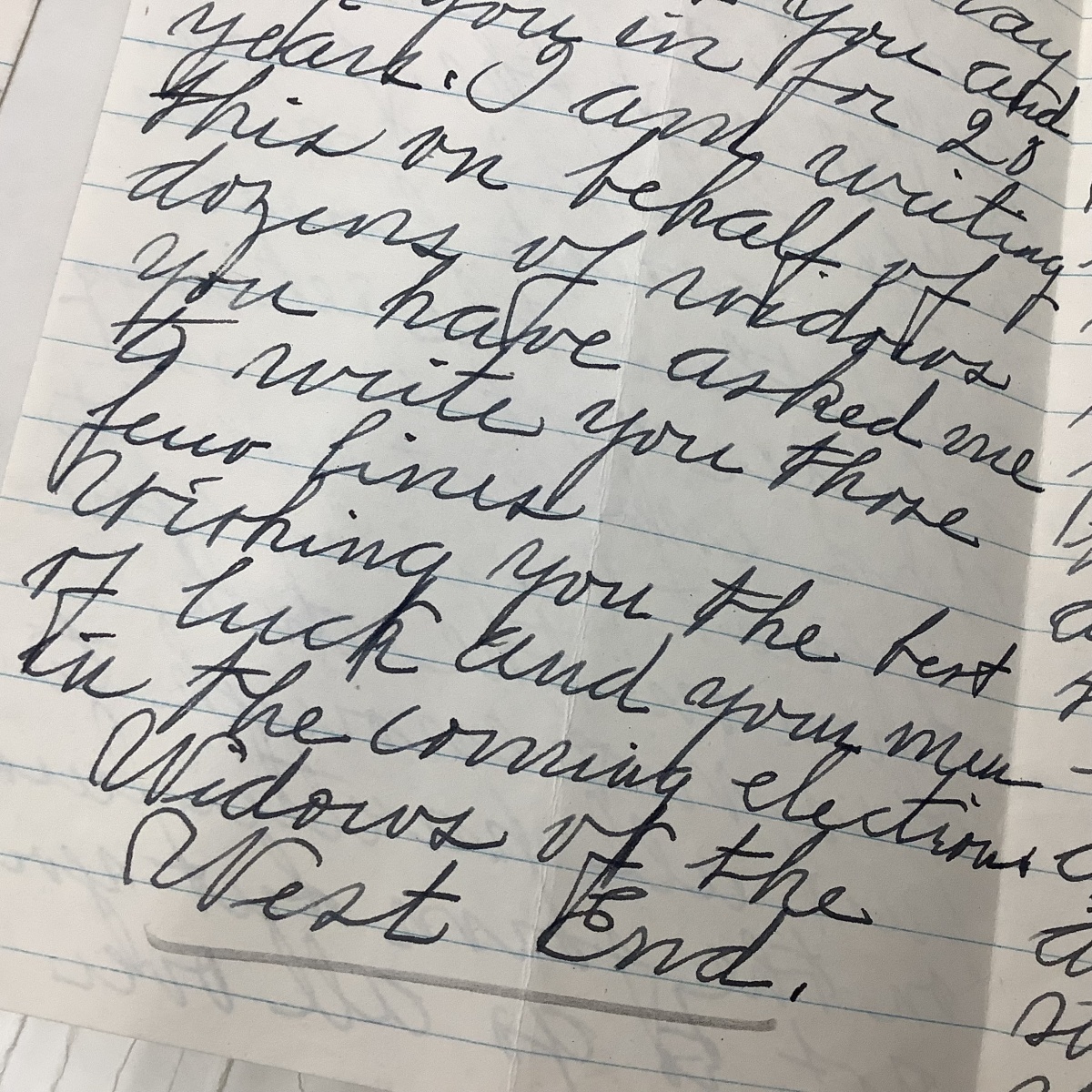

Despite challenges, including record blizzards and COVID-19 lockdowns, Dr. Boon and co-editor Dr. Vicki Hallett – together with more than thirty contributors – sifted through hundreds of letters written to Joey Smallwood, the first premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, between 1948 and 1952. Their work, Dear Mr. Smallwood, a tribute to the people and histories of Newfoundland and Labrador, is inspired by their love for the province and their desire to broaden conversations about Newfoundland and Labrador’s entry into Confederation.

Photo by Rich Blenkinsopp

Q: Please introduce yourself! Tell us about who you are and what you do.

A: I’m Sonja Boon and I’m a writer, researcher, flutist, and teacher. I’m currently an adjunct professor in the department of gender studies, Memorial University. I also teach as a mentor in the MFA program in creative nonfiction at the University of King’s College in Kjipuktuk (Halifax). I’m co-editor of the Life Writing Series at WLU Press. I’ve been a member of the RSC’s College of New Scholars, Artists, and Scientists since 2022.

Q: Next month, you’ll release Dear Mr. Smallwood. Can you tell us what the book is about?

A: In Dear Mr. Smallwood, we look at how everyday Newfoundlanders and Labradorians experienced the years immediately surrounding Newfoundland’s (as it was called then) entry into Confederation with Canada. The book is based on one of the richest archival treasures in Newfoundland and Labrador: the collection of some 10,000 letters written to Joey Smallwood by everyday Newfoundlanders and Labradorians between 1948 and 1972.

Organized chronologically by electoral district, these letters are part of the Smallwood Collection in the Archives and Special Collections division, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University. Dear Mr. Smallwood includes the work of 35 contributors. One group of contributors chose approximately ten letters from each district, and then each contributor wrote a reflective personal response to what they read. These responses are essays, letters, poetry, and even visual responses.

Another group of contributors wrote short contextual essays about life in mid-twentieth-century Newfoundland and Labrador.

Q: What inspired you to write it? Did your own experiences shape the story, and did you face any challenges along the way?

A: Confederation is a contentious topic in Newfoundland and Labrador, even now, over seventy-five years after the fact. For some, it was the absolute best decision ever made. For others, it remains an open wound. The figure of Joey Smallwood also continues to polarize: for some he’s a hero, for others a villain. But what was it like to live during the time when the future of Newfoundland (as it was known then) was being debated – at the National Conventions, of course, but also in homes and families and communities?

A large number of letters in the Smallwood Collection date from the years immediately surrounding Confederation. These letters offer a remarkable insight into what mattered for everyday Newfoundlanders and Labradorians at the time of Confederation. In them they share their frustrations, but also their desires. They position themselves as fully engaged voters who want more, not just for their own families, but for their communities and for Newfoundland and Labrador. The letters are fascinating!

We absolutely experienced challenges. We started our conversations about this book in 2019 and invited contributors to participate. Then, in early 2020, two massive back-to-back blizzards with high winds dumped over 100 cm of snow onto an already substantial snowpack. St. John’s was under a state of emergency for over a week and everything was shut down. Two months later, we shut down again, this time for the pandemic. Everything moved online, and the archives were closed. People’s lives were upside down for a long time, and the archives were largely inaccessible for two full years (archival staff were more than accommodating when they were able to be open and were willing to open at odd hours to support researchers – so huge kudos to them).

Q: What was your research process like in preparing the story?

A: This is a story of the people of Newfoundland and Labrador. And so right from the start, we wanted the book to reflect that: we wanted this book to include a diversity of voices. We invited a group of contributors to read the archival materials and to reflect on their own journeys with the materials. We invited another group to write short contextual essays. The book includes thirty-five contributors. Some have deep, deep ties to Newfoundland and Labrador. Others have only recently come to call NL home. But all of them have a passion for this place, its histories, its people, its stories.

Q: How does this book connect to your previous work or broader interests?

A: My co-editor, Vicki Hallett, and I are both life writing scholars. We’re interested in the ways people tell the stories of their lives, and how they make meaning from them. We’re also very interested in hidden, lost, silenced, and submerged stories; that is, in the politics of life writing: Who gets to tell stories? Whose stories get told for them? And both of us, from very different starting points, love Newfoundland and Labrador.

I’ve long been fascinated by letters as a particular genre and two of my earlier books are based on eighteenth-century letters. I love the reciprocity embedded within the form of the letter itself: a letter invites – and in the case of a letter to public figure, demands – a response. Letters are also performances, and how a correspondent chooses to tell their story (both what they do and do not share) matters.

Q: Were there moments while writing the book that surprised you, even as the author?

A: Honestly, I think it’s more about delight than it is about surprise. The continual delight, for me, is how vital and alive these letters are. Reading them is like listening in on kitchen table conversations. I can hear the voices speaking, and I love how engaged these correspondents are in the political process.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from Dear Mr. Smallwood?

A: I’d love for them to get a sense of how complex the landscape was at the time of Confederation: Newfoundlanders and Labradorians were clearly fully invested in the debates and deeply committed to their home. They wanted better lives for themselves and better futures for their children. They weren’t afraid to ask for these things, and they also weren’t afraid to hold their elected leaders to account. They weren’t just interested in electoral promises; they wanted to see them realized, and they were clear with Smallwood that he couldn’t just automatically count on their votes.

Q: Are there themes in the book that feel especially relevant today?

A: So many! Correspondents were interested in health care, education, social safety nets (pensions, benefits, etc), infrastructure (roads, communications, etc), jobs, and more. Some of the letters feel very familiar in that respect. But if I had to choose a particular theme that’s relevant, it’s the theme of political engagement: the letters reveal that Newfoundlanders and Labradorians were both passionate about the place they called home, and committed to and deeply engaged in the political process (worth noting here that Newfoundland was under commission of government between 1934 and 1949, and led by a group of appointed commissioners. Elections were suspended throughout this period).

Q: Are there conversations you hope this book sparks in Canada and beyond?

A: I’d love for this book to spark conversations about political agency, political identity, and political engagement. The correspondents who wrote to Smallwood were young and old. They were single. They had families. They were children or widows or wives or husbands or neighbours or workers or community leaders. They organized petitions. They shared receipts. They wrote poems, prayers, and songs. They challenged merchants in their communities. They challenged Smallwood. They offered suggestions and ideas. They asked for jobs. They shared some of the most intimate heartbreaks of their lives. They demanded better health care. They wanted – and deserved – more and they weren’t afraid to ask for it. In a world where authoritarianism is on the rise, all of this is important.

Q: As an author and scholar, what do you love most about what you do?

A: There is nothing I love more than puzzling with a story. I love playing in the archives (I know – some call this work). I love looking at how the archival pieces fit together (or don’t, as the case may be), and I love the writing process and considering how best to tell a story. Every step of the process is a wonder and a privilege, honestly.