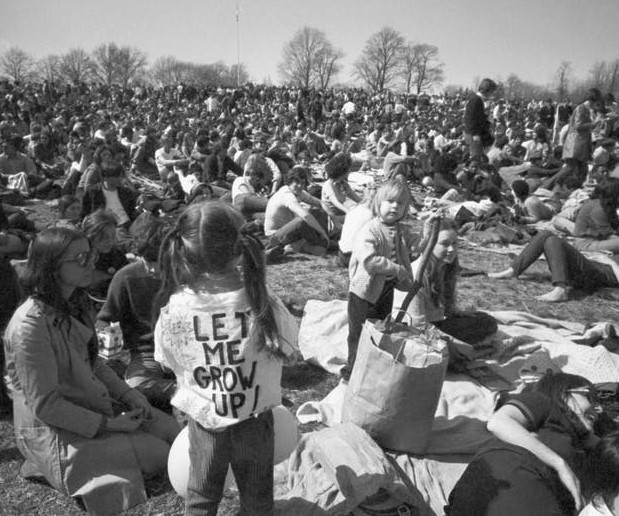

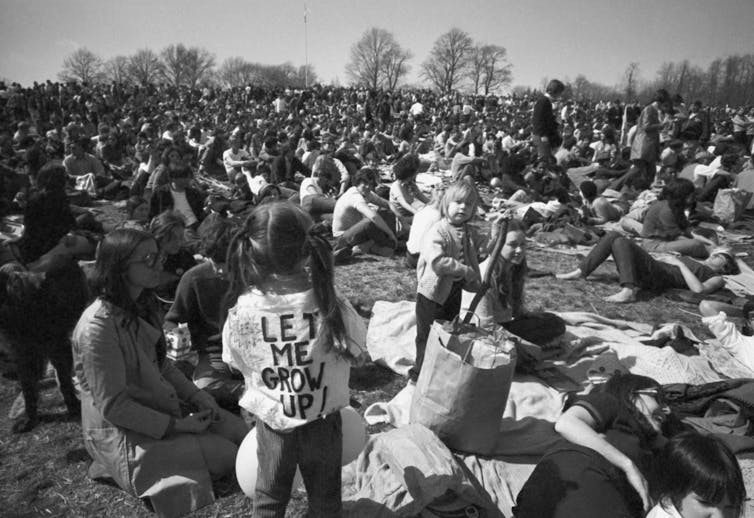

A crowd observes the world’s first Earth Day on April 23, 1970, in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. (AP Photo) Philippe Tortell, University of British Columbia

Fifty years ago, on April 22, 1970, millions of people took to the streets in cities and towns across the United States, giving voice to an emerging consciousness of humanity’s impact on Earth. Protesters shut down 5th Avenue in New York City, students in Boston staged a “die-in” at Logan airport and demonstrators in Chicago called for an end to the internal combustion engine.

CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite hosted a half-hour Earth Day special, calling for the public to heed “the unanimous voice of the scientists warning that halfway measures and business as usual cannot possibly pull us back from the edge of the precipice.”

Today, Cronkite’s words are eerily familiar. Warnings of impending ecological crises are now commonplace. But are we prepared to heed the warnings? In 1970, the answer was yes. The same might just be true, once again, in 2020.

CBS News Earth Day special report, part 1, from April 22, 1970.

The road to Earth Day

In 1970, the world was reaching the end of a post-war economic boom, associated with a rapid expansion of industry and manufacturing. “Better living through chemistry,” was radically changing the daily lives of many of the world’s inhabitants. Pesticides like DDT had saved thousands from malaria and other insect-borne diseases, while chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) had expanded safe and reliable refrigeration around the world.

But dark clouds loomed on the horizon. As the air, water and land became increasingly choked with industrial wastes, Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring sounded a clear warning about the poisonous effects of DDT and other synthetic compounds across the food chain.

Increasing ecological awareness was fuelled by the social unrest of the civil rights and anti-war movements. The youth of the day created a counter-culture that openly questioned their parents’ notions of progress.

Demonstrators hold a mock funeral at Logan International Airport in Boston to protest the airport’s pollution, expansion and the coming of supersonic jets, on April 22, 1970. (AP Photo)

First steps

The first Earth Day helped catalyze more than two decades of sweeping legislative changes, first at national levels, and then through multilateral institutions seeking to tackle global environmental problems.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol and 1992 Rio Earth Summit produced framework agreements to limit the accumulation of ozone-destroying CFCs, protect global biodiversity and mitigate human impacts on the climate system. These agreements sought to balance economic growth with ecological and social justice.

Within a few years of the Rio Earth Summit, other powerful forces of globalization began to emerge. In 1995, the World Trade Organization was created, ushering in a new economic order that has exerted a profound impact on planet Earth and its inhabitants.

Oceanographer Jacques Cousteau chats with former prime minister Brian Mulroney following Mulroney’s speech at the Rio Earth Summit in June 1992. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Ron Poling

Since the mid-1990s, rapid expansion of trade in the new digital economy has stimulated development in some of the world’s poorest countries, lifting millions out of poverty, but also greatly increasing income inequality. At the same time, globalization has expanded the ecological footprint of the world’s wealthiest countries over supply chains stretching across the planet.

Today, 25 years into our new globalized era, we must reckon with the unintended consequences of progress, much as we did in 1970. Between 1945 and 1970, and again from 1995 to 2020, our societies have transformed through geopolitical shifts, economic expansion and technological developments.

While the specifics are different, there can be no doubt that both periods left a strong imprint on planet Earth. But are we ready to tackle profound challenge of redefining our relationship with Earth?

The ties that bind us

Ignorance is no longer an excuse for inaction; a half century of science has provided clear evidence of the ongoing deterioration of Earth’s biophysical systems. What we lack is determination and courage in the face of powerful oppositional forces.

Rachel Carson stands in her library in Silver Spring, MD., holding her book ‘Silent Spring.’ She wanted to bring to public attention information that pesticides were destroying wildlife and endangering mankind. (AP Photo)

Much as Carson did in the 1960s, we still struggle against vested economic and political interests intent on maintaining the status quo. We must also recognize that the problems are now embedded deeply into the fabric of societies; tackling climate change, for example, requires nothing short of re-imagining the global energy sector.

Read more: A year of resistance: How youth protests shaped the discussion on climate change

We face a daunting task, but there are signs of hope, particularly as we see a resurgence of youth movements willing to challenge our notions of progress. The first Earth Day protesters were overwhelmingly young; they didn’t have a Greta Thunberg, but they did strike from school. And just as their message caught the attention of Walter Cronkite, at least some adults are listening now.

Disruption and new opportunities

What will it take to move us from listening to action?

Perhaps the current COVID-19 pandemic could provide a trigger. Our relentless drive to move goods and people across the planet has been hijacked by a microscopic bundle of protein and RNA, inflicting significant human suffering and damage on the global economy.

The pandemic is, no doubt, a global health catastrophe. But the disruption of the status quo also presents an opportunity to question our core values and to re-examine our relationships with each other and with Earth’s natural systems. For COVID-19, as with our most complex environmental challenges, any viable solutions will require co-operation rather than isolation across borders.

The pandemic also demonstrates how societies can mobilize rapidly in the face of existential threats. While our current emergency response to COVID-19 has been reactive, rather than proactive, perhaps it need not have been entirely so — why did we not learn from SARS, MERS, H1N1 and other global respiratory virus outbreaks?

People gather before participating in a student-led Climate March in Vancouver in October 2019. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Must we also wait for more dire impacts of climate change before taking action? Now is the time to mitigate environmental threats through proactive measures, developing the societal tools to maximize human well-being in a rapidly changing world.

The economic pain inflicted by COVID-19 should not limit our ability to take bold action. The environmental triumphs of the 1970s and 1980s occurred against a backdrop of significant economic uncertainty after the post-war boom.

When the current crisis passes, as it surely will, we must seize the opportunity to re-imagine, and to create, a different kind of future, much as the original Earth Day protesters did on April 22, 1970.

![]()

Philippe Tortell, Professor and Head, Dept. of Earth, Ocean & Atmospheric Sciences, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

"Voices of the RSC” is a series of written interventions from Members of the Royal Society of Canada. The articles provide timely looks at matters of importance to Canadians, expressed by the emerging generation of Canada’s academic leadership. Opinions presented are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society of Canada.