Julia M. Wright, Dalhousie University

War has been widely used — and criticized — as a metaphor for dealing with COVID-19. But the metaphor didn’t come out of nowhere. Writers have long linked war and disease, and not only because war often contributes to the spread of disease.

In my study of British and Irish literature from around 1800, including writing about medicine, it’s clear that people struggled to understand disease without having evidence of bacteria or viruses. In a chapter on “Contagion” in his 1797 handbook on medicine, the physician Thomas Trotter even laughed at the suggestion that diseases were spread by “little animals.”

William Heath’s satirical drawing ‘Monster Soup’ in the British Museum shows artists in the early 1800s understood medicine and disease before technology. (British Museum.), CC BY-NC-SA

Yet the idea persisted. In 1828, cartoon satirist William Heath imagined river water as “Monster Soup.” In 1854, English physician John Snow used what we might now call contact tracing to show that a London water pump was at the centre of a cholera outbreak. The same year, Italian physician Filippo Pacini used a microscope to identify the cause of the disease.

An easy step from disease to war

Writers were aware of public and research interests in medicine and drew on them, as in the familiar example of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1818. Writers also used medical metaphors: for instance, William Blake called the influence of Greek and Latin literature a “general malady and infection.”

These writers are using figures of speech to link concepts together: war is like a storm, disease is like war, and disease is like a storm, spread through clouds of bad air, raining contagion.

Read more: Apocalyptic fiction helps us deal with the anxiety of the coronavirus pandemic

Metaphors aren’t simply decorative. They help explain unfamiliar ideas, and help us remember them by making them vivid or surprising. When Shakespeare had Hamlet talk about picking up weapons to fight “a sea of troubles,” he was communicating a sense of overwhelming odds. The metaphor was good enough to stick and is still widely used. Metaphors can also pass judgement, like Blake associating Greek and Latin literature with disease because it promoted war.

Writer and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was one of many British writers who used storms as metaphors for battles which were, in turn, used as metaphors for diseases. (National Portrait Gallery, London), CC BY-NC-SA

War was almost constant for Britain at this time, and writers often turned to thunderstorms to capture the terrible sound of battles. Blake’s 1793 poem about the American Revolutionary War describes the new United States as “darkned” by storm clouds while “Children take shelter from the lightnings” and leaders speak “in thunders.” A few years later, in his poem “Fears in Solitude,” Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote about “Invasion, and the thunder and the shout.”

Medical writers of the era thought that bad air carried disease because they didn’t have the technology to see further. But they were able to connect the spread of disease with soldiers and ships. This made it an easy step from disease to war — with weather still in the mix.

In “Fears in Solitude,” Coleridge associated British imperialism with a spreading infection, carrying “to distant tribes slavery and pangs” “Like a cloud that travels on, / Steamed up from Cairo’s swamps of pestilence.” In “Adonais,” P.B. Shelley wrote of “vultures to the conqueror’s banner true … whose wings rain contagion.”

King Cholera goes to war

Two hundred years ago, disease wasn’t an “Invisible Enemy” or a “little animal”. It had power to kill, much like the kings who sent armies around the globe.

In her influential 1792 essay, Vindication of the Rights of Woman, English writer Mary Wollstonecraft wrote that “despots” are the source of a “baneful lurking gangrene” and lead to “contagion.” A quarter of a century later, the cholera pandemics began.

In John and Michael Banim’s 1831 poem “The Chaunt of the Cholera,” cholera doesn’t just “Breathe out the breath which maketh / A pest-house of the place.” It is a mercenary working for Europe’s monarchs: “Kings!–tell me my commission, / As from land to land I go.” Others, like English cartoonist John Leech, called the disease Lord Cholera or King Cholera.

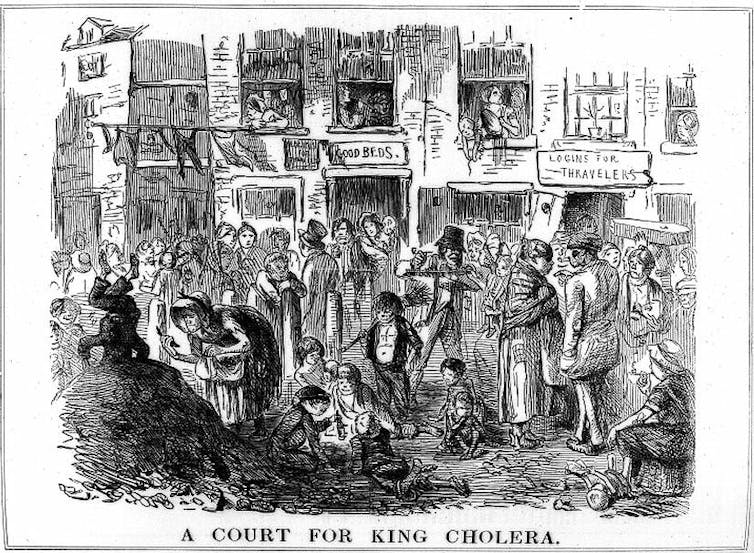

John Leech’s cartoon showing the association of cholera with squalor. A child stands on his head on top of a rubbish heap in the left-hand corner. An old woman scavenges from the heap, another child shows off his own find, and washing flutters in the breeze overhead. (Wellcome Library), CC BY

John Leech’s 1852 cartoon, “A Court for King Cholera,” relayed a message we’re hearing now: inequality feeds pandemics. The 1853 poem “King Cholera’s Procession” also details the unsanitary conditions of the urban poor while condemning “Those that rule” for being King Cholera’s “friends.”

In her 1826 novel about a devastating pandemic, The Last Man, Mary Shelley also links rulers, war, and disease. The plague “shot her unerring shafts over the earth,” a shower of arrows, and becomes “Queen of the World.” Shelley idealizes the leader “full of care” who doesn’t want victory — only “bloodless peace.”

The coming storm

To these writers, war was a metaphor for the problem, not the solution.

In our time, business media suggest “battle metaphors” are overused. We have television shows like Robot Wars and Storage Wars, training sessions called “bootcamps” and elections in “battleground states.”

War is all too real and devastating in many parts of our world. But as a metaphor it is worn out — perhaps no longer vivid, no longer explanatory. Writers such as Coleridge, the Shelleys, and Blake may have seen close connections between war and disease, but their work also hints at another possibility.

Instead of talking about a war on COVID-19, let’s consider those storm metaphors. We need to stay inside and wait for it to pass.

And, while we are, perhaps we can also look to the past for help in understanding our present. Before they had evidence of germs, they could see that war and inequality spread disease.

![]()

Julia M. Wright, University Research Professor, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

« Voix de la SRC » est une série d’interventions écrites assurées par des membres de la Société royale du Canada. Les articles, rédigés par la nouvelle génération du leadership académique du Canada, apportent un regard opportun sur des sujets d’importance pour les Canadiens. Les opinions présentées sont celles des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de la Société royale du Canada.