In 1989, when Dana Lepofsky (FRSC) first set foot on Xwe’etay/Lasqueti Island, there was a widespread misconception that First Nations had never lived there permanently. But Dana, an archaeologist and ethnoecologist, saw signs that told a different story. As a result, she started a 30-year journey of outreach on the island to educate about Indigenous heritage as seen through an archaeological lens and to explore ways to better honour and protect that heritage. This culminated in the Xwe’etay/Lasqueti Archaeology Project (XLAP).

Dana explaining the layers of the archaeological site revealed in a hole dug by an excavator in advance of house construction. The landowner was horrified that a site was discovered on his property and that he had no idea that it existed; he subsequently sponsored the first community-centered archaeology initiative on the island and moved his house to beyond the boundaries of the archaeological site — even though it was not required by law (photo by Ken Lertzman).

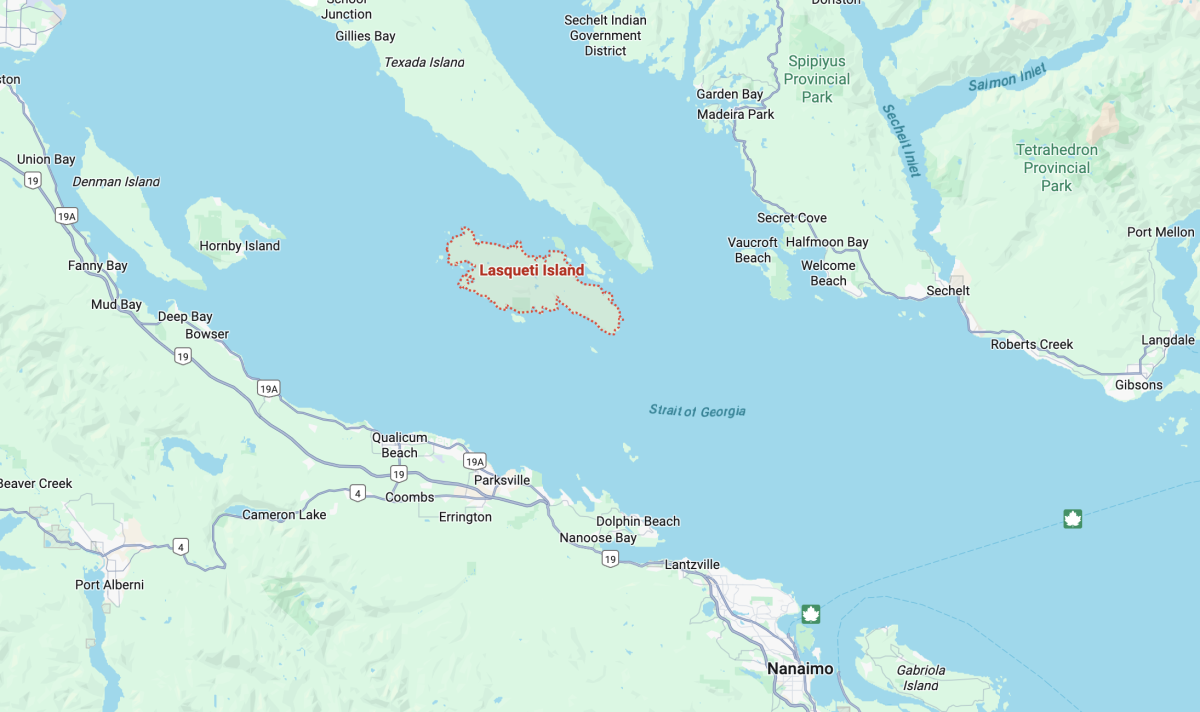

Locating Xwe’etay/Lasqueti Island

Xwe’etay/Lasqueti Island is located in the Salish Sea, off the east coast of Vancouver Island.

Credit: Google Maps

Until recently, the well-established “truth” about the history of the island was that First Nations only came occasionally to gather clams, berries, or to fish. This is a "truth" held by many settlers in the region about their homes – which taken to its logical extreme means that First Nations didn’t live anywhere. On Xwe’etay, there are no descendant community members, which enforced this colonial view that this was an empty land free for the taking.

Given its remote location, and destination over the 20th and 21st centuries for people looking for alternative lifestyles, Xwe’etay/Lasqueti was widely seen as “the island in the middle of nowhere.”

Challenging Misconceptions

Even at a first glance, Dana saw evidence of past lives lived everywhere she looked.

It became her goal to study the island’s Indigenous archaeological heritage, and to use the archaeology as a way of connecting the local settler community with the neighbouring Coast Salish communities, for whom Xwe’etay/Lasqueti had been home for millennia. The XLAP team sponsored many outreach events that centered the dazzling local archaeological record and brought together island settlers with members of several local Nations (learn more). In addition to local education, she sought to inform future policies on the protection of archaeological sites.

For the policy side, Dana teamed up with Sean Markey, a community-based planner at SFU, and his students. As Dana says, “While the archaeology students focused on mapping sites and determining out how old they are, the planning students were interviewing settlers and First Nations about things like heritage policy, how people felt about having sites on their property, and what should be done with private collections of belongings [artifacts]”.

XLAP co-lead, Sean Markey, standing in front of the engraved redcedar plaque that celebrates Xwe’etay's Coast Salish origin story and welcomes people to Indigenous lands. The image was created by Coast Salish carver Xwulqsheynum Jesse Recalma and graphic artist hḵwen̓/ ts;simtelot Ocean Hyland. To Sean's left is the audio button to press to listen to the name Xwe’etay spoken by Tla’amin Elder qaʔaχstaləs / Dr. Elsie Paul. (photo by Dana Lepofsky).

Guided by the Ancestors

All parts of XLAP were guided by the project’s First Nations advisors and partners. All Nations in the region were invited to join the project and representatives from Qualicum, K'ómoks, Tla’amin, Wei Wai Kum, and Halat Nations joined the team. Through them, spiritual leaders from other Nations joined to guide the participants and community members in how to fully honour the ancestors’ whose past they were studying.

Tla’amin Elder Betty Wilson sitting on the redcedar bench in front on the “Welcome Mural” on the Xwe’etay dock. The image was co-created by Coast Salish artist Jesse Recalma and island-settler artists Julia Woldmo and Sophia Rosenberg. The painting is based on findings from XLAP about this location, oral traditions, and local ecological knowledge (photo by Kathy Schultz).

Ogwi’low’gwa Kim Recalma-Clutesi, a member and former chief of the Qualicum First Nation on eastern Vancouver Island, provided guidance for the project from its very beginning, and became increasingly involved as time went on.

Kim knew that many of the residents of the small islands off the coast of Vancouver Island assumed that First Peoples had never lived on Xwe’etay/Lasqueti. She viewed the project as a chance to share the knowledge her community had safeguarded for generations: that the island was once home to thriving First Nations populations, who were, in just a century, wiped out by the fur trade, disease, residential schools, land restructuring, and the outlawing of culture and tradition.

Unveiling of plaque on Xwe’etay that honours Indigenous ancestors of the island — placed near the older plaque that honors the “discovery” of the island by the Spanish. The event drew over 150 people. Pictured are members of Qualicum, Tla’amin, and Ts’msyen Nations. Kim Recalma-Clutesi (Qualicum Nation), project advisor, is on the far left (photo by Kathy Schultz).

Community-Based Archaeology in Action

There were challenges in engaging the settler community on Xwe’etay/Lasqueti along the way.

As Dana says, “We heard people talking about fear of their land being taken away, of not being able to ever build again, of so many things."

As Kim notes, “People look at things very differently when their ownership could change.”

Kim proposed setting up a Q&A session with community stewards and knowledge keepers who had long worked on Xwe’etay/Lasqueti — giving residents the chance to ask any questions they may have. As Kim explains, “simply stating what we knew wouldn’t have been effective.” As she put it, “it was necessary to begin with consultation and distill myths.”

Through inviting consultation, Kim brought clarity and trust to the minds of the islanders, and a way to move on. When one islander asked, “what can we do to right the wrongs done to the Indigenous archaeological heritage?”, it was decided that a traditional burning ceremony for the ancestors be held on the island – the first in 200 years. Witnessing that ceremony (and the second one the year later) with members of neighbouring Nations, led to profound positive changes in the way the islands understood Indigenous heritage.

Project team member Christine Roberts (Wei Wai Kum Nation) and Xwe’etay resident and landowner Suzanne Heron percussion coring on the archaeological site on Suzanne’s property. About half of the landowners on the island with archaeological sites on their property embraced the idea of learning more about the Indigenous heritage on the property they now steward (photo by Dana Lepofsky).

Findings and Impact

Over more than 30 years of outreach, along with a five-year SSHRC-funded project, Dana and the rest of the team demonstrated that Xwe’etay wasn’t “an island in the middle of nowhere” but indeed “an island in the middle of everywhere” (as their travelling museum exhibit is titled) – and had been for 8000 years.

They demonstrated that Xwe’etay was a center of the Salish Sea’s physical and cultural landscape, with an Indigenous population at its peak estimated between 800 and 2,200 people, compared to the current 500 residents.

As Dana explains, “We know this from our archaeological surveys which demonstrate that there was a large and dense permanent, pre-contact population; from the sourcing of the stone tools and other belongings found throughout the island and now held in private collections; from the number of clam gardens and fish traps in which marine resources were tended to feed the people; and by the concentrations of plants such as ‘wild’ crabapple and camas — a beautiful lily whose bulb was valued as a food source — that are likely remnant managed ecosystems of the past.”

Tla’amin Elder and ʔayʔajuθəm language expert Betty Wilson, Tla’amin Councillor Dillon Johnson, and Elder Ogwi’low’gwa Kim Recalma-Clutesi at the unveling and blessing of the mural installation (photo by Kathy Schultz).

Beyond establishing the scale of the pre-contact population, the findings from XLAP transformed local perspectives and understanding of Indigenous presence. As Dana notes, “Even the name Xwe’etay — the Coast Salish name for the island — is now part of the everyday lexicon, including the island’s Facebook pages and the island’s community newsletter!”

Dana adds, “The most meaningful result of the pris not an ‘insight’ or a ‘finding’, but rather to witness the change in the islanders' perspectives. We have so, so many testimonials of how this project has changed people's lives — in the way they think about their relationship to the land and seas, to each other, and of course to our First Nations neighbours.

“For our First Nations partners, it has been ‘coming home’ to their lands after not being here in large numbers since the early 1800’s. They have brought their ceremonies for the ancestors back to the island and graciously shared them with us. Many have returned multiple times for several events and have made friends here. These are small but meaningful and powerful changes in the way we relate to this land and each other.”

When asked what she thought would be the biggest measure of the project’s success, Kim said: “Whether or not we continue to do this — to call in cultural advisors and honour their perspectives. It shouldn’t be about ticking off a box; it’s about consultation and doing it with thought and grace.”

The Journey of Reconciliation

As Dana says, “Understanding and honouring the land and those who lived here centuries ago is at the heart of reconciliation. This is a fundamental part of the ‘truth’ in truth and reconciliation.”

By honouring and restoring Indigenous heritage, XLAP has strengthened relationships between local settler and Coast Salish communities, created space for First Nations to reconnect with a land they inhabited for nearly 8,000 years, and helped shape policies for the long-term protection of archaeological sites.

As Kim adds, “There is no place for shame on the path of reconciliation, as it stands in the way of moving forward. Instead, it is about discovering the threads of shared intent and knowledge— threads that bring us together.”

With the Xwe’etay Project, that thread was deep connections to the land, and the shared desire to understand and honour it.