MY COVID-19 VACCINE EXPERIENCE AS AN URBAN INDIGENOUS WOMAN IN ONTARIO

MY COVID-19 VACCINE EXPERIENCE AS AN URBAN INDIGENOUS WOMAN IN ONTARIO

Chantelle Richmond | March 30, 2021

Chantelle Richmond is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Health and Environment at Western University

On March 25th, I received my first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in London, Ontario.

Just a day earlier, Indigenous adults 16+ were added as an eligible population to the Middlesex London Public Health Unit’s (MLHU) Phase 1 Plan, which is based on regional vaccine supply, provincial direction and regional prioritization. I logged on to the MLHU vaccination website to search for options and within minutes, I received confirmation of an appointment for the next morning.

Indigenous People living in Northern and remote reserves and communities were prioritized for vaccination from the earliest development of Ontario’s Phase 1 Plan. The success of these efforts have been remarkably efficient. The rallying efforts of key public health experts, including Indigenous physicians working in major urban centres in Ontario, led to the expansion of the Phase 1 plan to include all Indigenous adults in Ontario, including those living in urban centres.

There are important criteria that go into this decision-making process – overall population health status and risk level, access to health care, housing quality, food security, and various other key socioeconomic determinants. At the population level and adjusting for age, Indigenous people fare poorer than do non-Indigenous Canadians on all of these dimensions. These inequities have been shaped, and are sustained to this day, by various processes – settler colonialism, racism, dispossession – that perpetuate the structural disempowerment of Indigenous People and communities.

As I drove to my appointment, I was both excited and nervous. What I did not expect was the intense wave of emotion I would experience. From the moment I walked into the St. Thomas arena, I was met with the kindness of strangers, who ushered me through this life changing process. I moved through one line to the next, until finally I was in the line that would take me to the vaccine.

Across the arena floor, I could see the nurse waving me over with a little orange flag. I walked toward her, and found myself suddenly overcome with tears.

“My name is Lexi” she said, “how are you?”

I could barely speak. “I am just so thankful to be here,” I said.

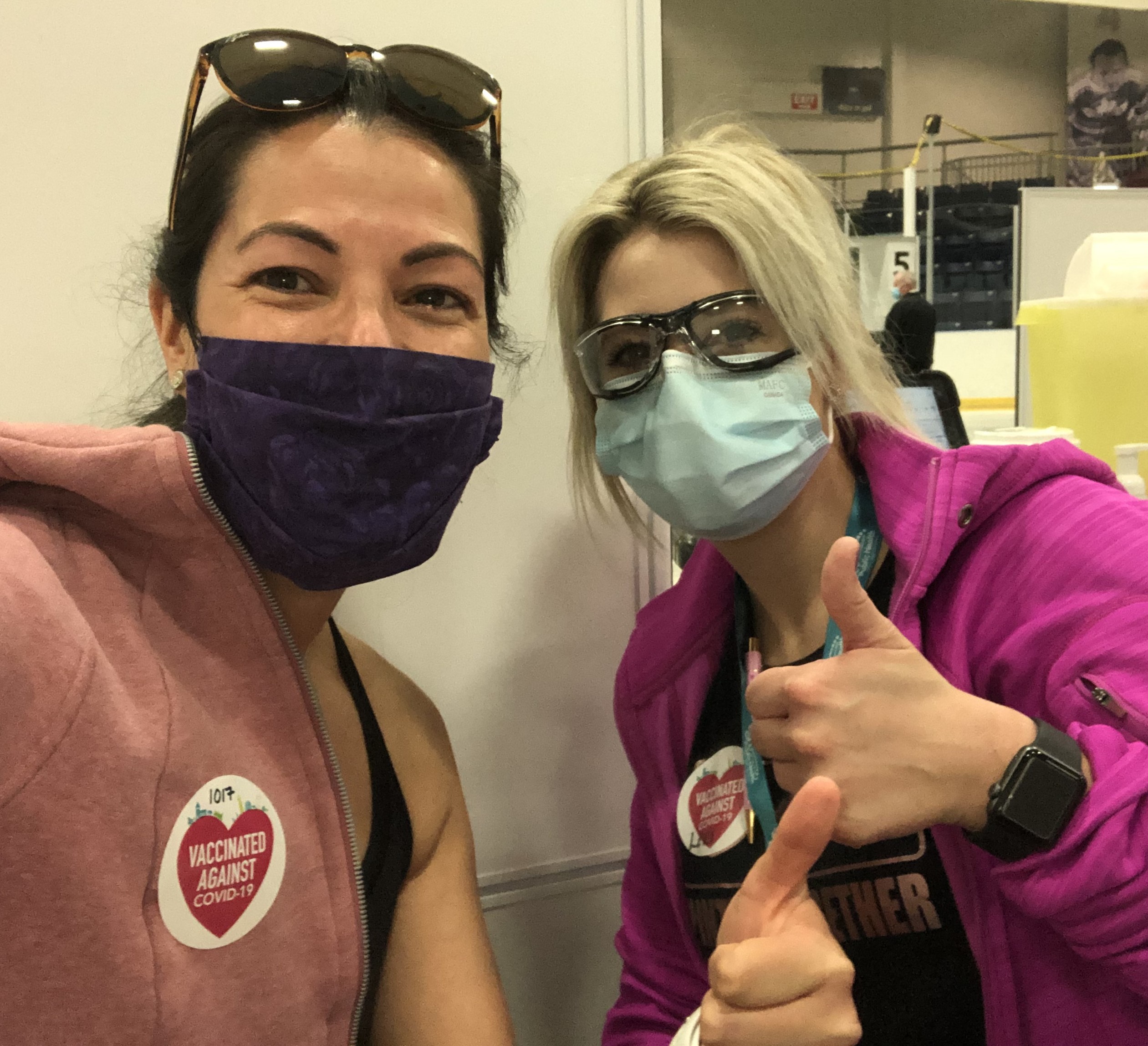

She assured me that I was not the first of her patients to cry. Lexi told me I was having the Pfizer vaccine. I removed my sweater from my left arm and before I knew it, the needle was in my arm. “Your arm might be a bit sore tomorrow,” she said as she handed me a heart-shaped sticker “Vaccinated against COVID-19.” I asked if we could take a picture. We smiled with our thumbs-up to acknowledge this exciting moment.

As I got in my car to drive home, I was flooded with more tears. I was grateful that I had been given the vaccine. More importantly, I felt proud and dignified to be offered vaccination priority as an Indigenous woman.

As an Indigenous Professor – a healthy woman with a good income - I admit that I also carried guilt with me through my vaccination experience. As I sat there, I worried about what others would say or how they would react to my prioritization. Did I deserve to be vaccinated when there were 70 year olds who would not get the vaccine this month? My own mother, a 74 year old Anishinaabe woman living in rural Northern Ontario, has yet to be vaccinated.

It was then that I realised that these worries – this unexpected burden of guilt and shame – are not of my own creation. For too long, the health needs and basic human rights of Indigenous Peoples have been subjugated, disrespected or altogether ignored. Over many years, what does this do to the psyche? Indigenous Peoples always have to work harder to gain access to education, jobs, housing, education, even safe drinking water for goodness sake! For generations, we have repeatedly been told “just be patient.” Case in point: members of Grassy Narrows First Nation continue to live with the health effects of mercury contamination that occurred several decades ago. When will Grassy Narrows receive the reparation and justice it deserves?

These realities accumulate over a lifetime, and they demonstrate to Indigenous People that we should expect less. The racism that underlies so many of the systems that support Indigenous inequity lead us to know that, in fact, we are less. This is internalized racism. Despite the privilege I have gained in my educational pathway, that little bug is constant in my ear. These past few days it has been ringing pretty loudly, compounded by the comments of some, and the silence of others.

For the first time in Ontario’s public health history, it has prioritized Indigenous People by creating a structure that both identifies and meets the unique health needs of our population. The decision to prioritize the vaccination of Indigenous People isn’t only a good public health decision for the Indigenous population, it makes sense for Ontario as a whole. After all we are stronger together, aren’t we? While this sentiment may serve as rhetoric for some, population health researchers demonstrate time again that more equal populations are in fact more healthy too.

In the post-COVID era, I truly hope Ontario can leverage the bravery and insights gleaned from this experience to engage Indigenous communities and Indigenous leadership to address other persistent health and social inequities in an equally just manner.

This article initially appeared in the Globe and Mail on March 30, 2021.