Left to right, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Finance Minister Allan MacEachen and Québec Premier René Lévesque attend the constitutional conference in Ottawa on Nov. 5, 1981 — the morning after eight premiers hastily pieced together a constitutional accord. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Ron Poling

Raymond B. Blake, University of Regina and John Donaldson Whyte, University of Regina

On Nov. 5, 40 years will have passed since Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and provincial premiers agreed in an Ottawa hotel to a new constitutional accord.

While the moment is celebrated as a significant national achievement, it also produced bitterness that continues to impose upon Canada a cost that remains destructive to the country.

In this clip from CBC TV’s The National, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau lauds the milestone.

After decades of searching for constitutional resolution amid increasing tension and divisions, 10 of Canada’s 11 first ministers agreed to add to the Constitution a Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a commitment to fiscal equalization among provinces, expanded provincial jurisdiction over natural resources and an amending formula aimed at making Canada a self-determining nation.

While this political milestone deserves recognition, so do its troublesome consequences.

No consent from Québec

The subsequent plan for constitutional patriation was made without Québec’s participation or its consent. Its basic elements diverged significantly from the reforms that Québec and other provinces had proposed several months earlier.

A provincial united front on the Constitution had unravelled as the provinces had come to believe that the sovereigntist government of Québec, led by René Lévesque, would not agree to any constitutional patriation plan.

Trudeau stretches to shake hands with Lévesque at the start of the meeting of the first ministers meeting in Ottawa on Nov. 2, 1981 — two days before the Québec premier was excluded when eight premiers constructed a constitutional accord. CP PHOTO/Bill Grimshaw

The basic elements of Canada’s new Constitution were proposed through a secret provincial initiative hastily constructed in an Ottawa hotel on Nov. 4, absent of both Lévesque and Trudeau and containing little room for revision.

The prime minister, with palpable unhappiness, accepted it.

First Nations were outraged that recognition of Indigenous rights were not included. This was a painful result for Indigenous groups; they had been a part of the constitutional negotiations, albeit at side tables, and had expected Indigenous rights to be recognized as a fundamental limitation on federal and provincial powers and included in the new Constitution.

Women’s organizations were angry over the failure to include the guarantee of absolute gender equality that they had advocated for and had thought had been accepted by governments as a key element of a modern human rights regime.

Bitterness created

The protests over the absence of Indigenous rights and gender equality were resisted briefly by the provinces but, within weeks, these two categories of rights were added to the accord.

However, their initial absence created bitterness and confirmed the suspicion that a provincial power grab was truly fuelling the constitutional reform process — not a genuine desire for constitutional modernization.

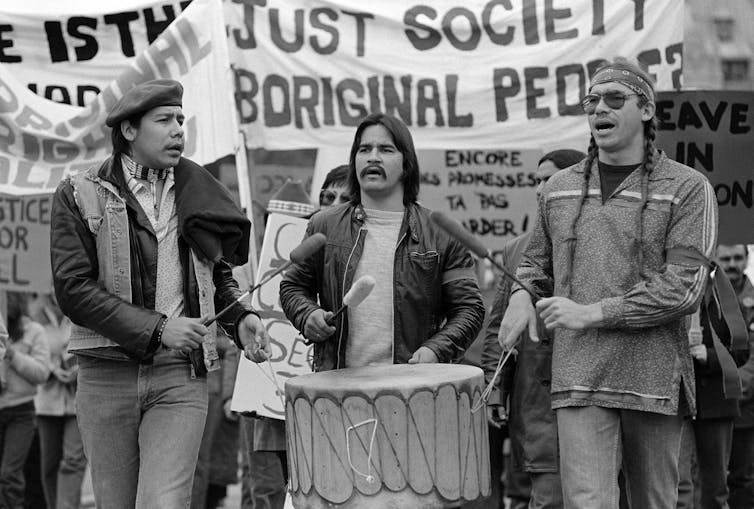

Groups of Indigenous people march on Parliament Hill in November 1981 to protest the elimination of Indigenous rights in the proposed constitution. CP PHOTO/Carl Bigras

The sense that provincial self-motivation was the driving force of constitutional reform was strengthened by the provinces’ attack on the proposed Charter of Rights and Freedoms — one that enjoyed broad public support.

Read more: 40 years later: A look back at the Pierre Trudeau speech that defined Canada

The premiers made their agreement for constitutional reform conditional upon Ottawa agreeing to include a section in the Charter — now known as the notwithstanding clause — that would allow provincial legislatures to override its most fundamental human rights.

Trudeau again accepted this condition reluctantly and unhappily. It was an alteration of the announced constitutional accord of the most fundamental kind; it occurred without notice or public consultation — and it was Canada’s constitutional surprise.

Canadian federalism weakened

The constitutional reform plan adopted in November 1981 has produced resentments and weaknesses in national relations that linger to this day.

Today, Canada’s historic tradition of effective political unification is profoundly tested. Courtesy and trust among the provinces and towards Ottawa have been eroded. We’ve seen countless fights between provinces and the federal government over equalization, environmental regulations and climate change policy and even over the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The events of the night of Nov. 4, 1981, were significant contributions to this decline. What happened then was simple ambush politics led by several provinces to construct a constitutional reform plan that they recognized the prime minister would not be able to reject; national sovereignty and constitutional rights and freedoms had been his battle cry, after all.

Reaching a deal under terms of partial defeat was clearly preferable to Trudeau than complete failure and the continuation of Canada’s constitutional morass.

The cost of constitutional success

And so constitutional failure was avoided. But constitutional success has cost Canada and its political integrity.

The specific acceptance by Trudeau’s government of the constitutional bargain ironically eroded commitment to, and confidence in, the federal government.

Trudeau gets a round of applause from Liberal members in the House of Commons after signing a constitutional accord with the provincial premiers. CP PHOTO/Fred Chartrand

Québec has not forgotten its exclusion from Canada’s constitutional renewal. The dominant Canadian trope of two nations becoming one was destroyed. Instead, Canada returned to being two nations, and Québec’s unique manner of engaging in national politics since then underscores the growing difficulty of managing the Canadian state.

The consequence has been pressure on the federal government for 40 years to act without resolve when faced with nationalist Québec interests.

Granted, this is not markedly different from the attitude of a number of other provinces during the same period, but unlike other regions of the country, Québec’s nationalist policies are viewed as the legitimate protection of its distinct culture. Nonetheless, a country is weakened through inattention and indifference to national cohesion.

The manner in which the Canadian Constitution was created in 1981 following last-minute negotiations has had consequences. The process contributed to weakened national solidarity and has made governing the country more precarious due to insistent demands to accommodate the political wills of provinces.

Raymond B. Blake, Professor of History and Head, Department of History, University of Regina and John Donaldson Whyte, Professor Emeritus, Politics and International Studies, University of Regina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

« Voix de la SRC » est une série d’interventions écrites assurées par des membres de la Société royale du Canada. Les articles, rédigés par la nouvelle génération du leadership académique du Canada, apportent un regard opportun sur des sujets d’importance pour les Canadiens. Les opinions présentées sont celles des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de la Société royale du Canada.