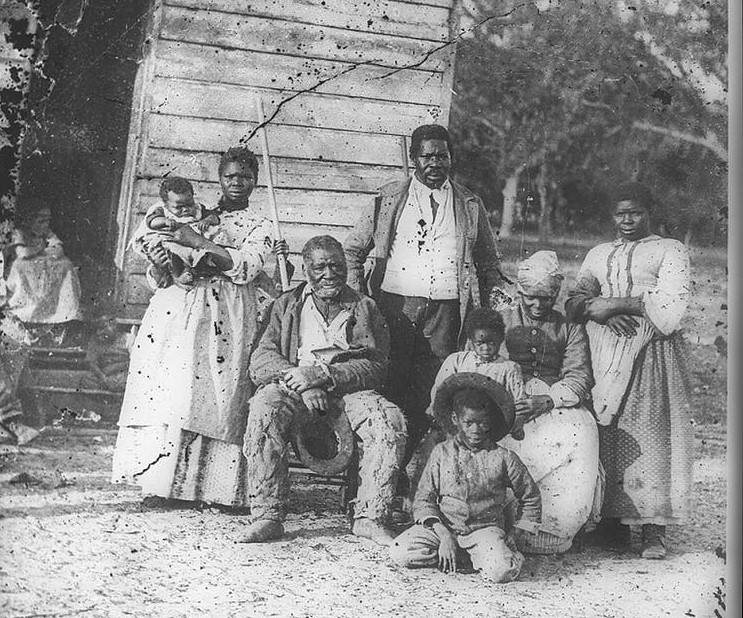

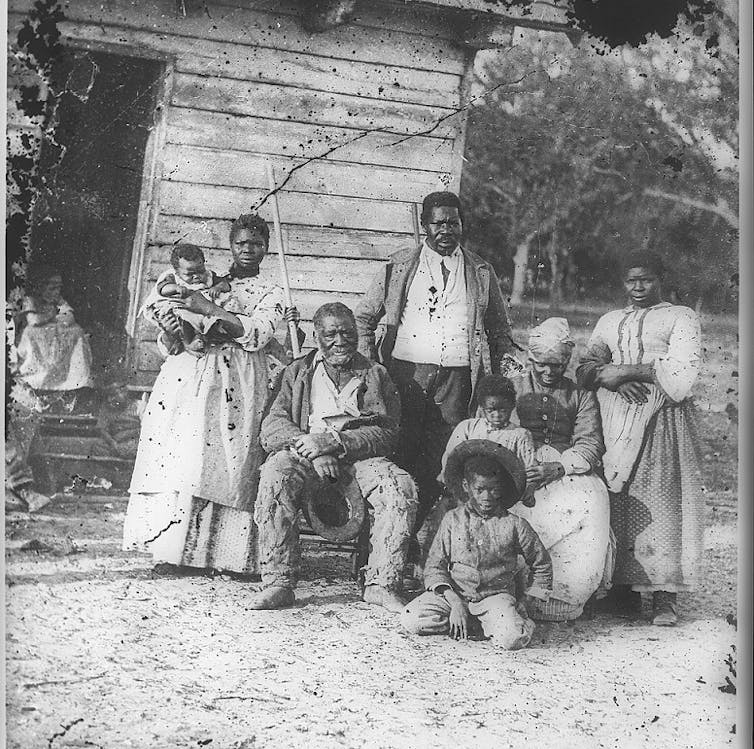

Five generations on Smith’s Plantation Beaufort at South Carolina in 1862. Timothy H. O'Sullivan/Library of Congress Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, Wilfrid Laurier University

In a 2016 poll, 58 per cent of African-Americans said they believed that the United States should pay financial reparations to African-Americans who are descendants of slaves. Only 15 per cent of whites agreed.

I am a white woman and I support reparations to African-Americans. I have published academic articles on the issue, including: “Official Apologies.” I am the author of Reparations to Africa and a co-editor of The Age of Apology.

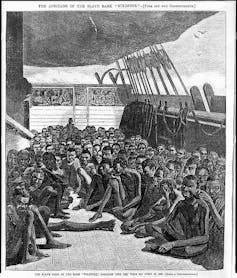

The Africans of the slave bark Library of Congress

In 2005, the United Nations issued a short document which outlined the basic guidelines on the right to a remedy and reparation for victims of gross violations of human rights law. Financial compensation is one aspect of reparations mentioned in this document, but it is not the only one. Apology is important. So is commemoration and tributes to victims, and an accurate account of the violations.

Five years ago, author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a harrowing account of injustices to African-Americans in an article for The Atlantic. These injustices occurred during the period of enslavement, but also the Jim Crow era, the Civil Rights era and down to the present.

In his article, Coates called upon all Americans to acknowledge their “shameful history” including injustices of enslavement, terrorism, plunder and piracy committed against African-Americans. He wants all the facts to be accurately reported.

Accurate acknowledgement would be a first step in reparations.

Apology is a second step.

Apologies

So many governments, institutions and private businesses in the United States are implicated in slavery and post-1865 injustices that it would be impossible for them all to apologize at once. But a good start would be an apology for slavery by the president of the United States, joined by the governors of every state that ever permitted enslavement.

The text of the apology would have to be carefully negotiated with African-American community leaders.

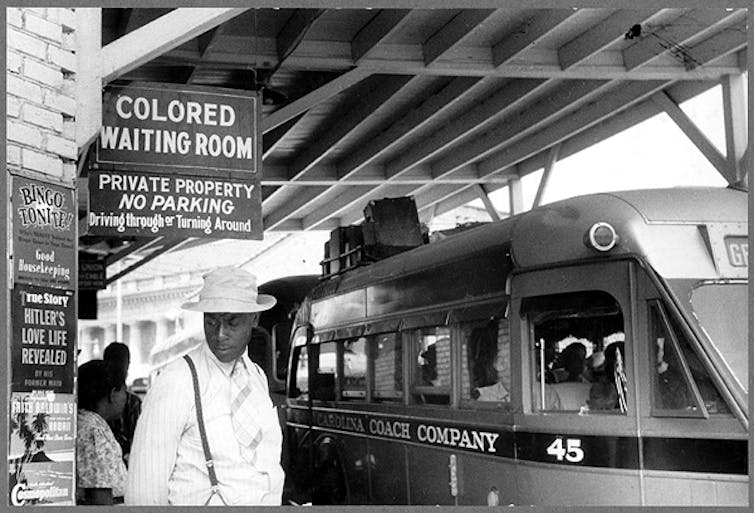

At the bus station in Durham, N.C., in the 1930s. Library of Congress/FSA

The apology would also have to be carefully surrounded by ritual, so that its sincerity and seriousness would be apparent.

This could be followed by literally thousands of apologies by lower-level municipal governments, religious institutions and businesses. Every single institution would have to investigate its history and acknowledge and apologize for every single act of enslavement and discrimination against African-Americans.

Memorials

The next step would be to memorialize all these injustices. It is not enough to tear down monuments to leaders of the Confederate army. Memorials should be put up at public expense to African-Americans who fought against enslavement and later injustices.

Memorials should also be erected at sites of plantations, sites of protest and sites of known murders of African-Americans, from those who were lynched in decades past to those unjustly killed by police. These memorials are a way to assert that Black lives matter.

Financial reparations

Finally, there is the question of financial reparations and whether descendants of enslaved people should receive them. How, if at all, can all the descendants of enslaved African Americans be identified? Even if they can be identified, should they receive individual financial reparations?

Perhaps yes, to compensate for the huge gap in (mostly inherited) wealth between white and Black Americans. Perhaps African-Americans should be given a financial “boost” to help them on the road to moderate, middle-class security. But many white and other Americans might view this as unfair to other people who don’t enjoy such prosperity.

Alternately, perhaps the federal and state governments should pay group reparations to African Americans. Whites might be more willing to accept collective reparations of this kind.

One possibility is to invest in education, from shoring up predominantly African-American elementary schools to special university scholarships. One might argue that affirmative action programs have already accomplished this, but they have been weakened over the decades and, in any case, only apply at the university level.

Civil rights march on Washington, D.C., 1963. Warren K Leffler/U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection/Library of Congress/

Another option is housing investment in predominantly African-American residential areas, especially where public housing projects are located. For decades, African-Americans have been subjected to low-quality public housing and mortgage discrimination.

Yet another option is investment in African-Americans’ health care, although one could argue that the whole country deserves this kind of investment. Nevertheless, if African-Americans suffer from some health problems at higher rates than white Americans, then reparations could include enhanced health care.

Read more: Racism impacts your health

Many white and other Americans may oppose reparations to African-Americans on the grounds that neither they nor their ancestors had anything to do with the many ways African-Americans were and are oppressed.

But as citizens — whether of the U.S. or, in my case, Canada — we have a responsibility to make amends to fellow citizens who have been harmed by the past or present policies of our governments. Acknowledgement is a first step forward. Apologies, memorials and financial reparations continue the process.

Reparations are a way of making the country whole, by partially remedying the inherited inequalities that still plague African-Americans. They are a way of saying that African-Americans are, at long last, equal citizens of the United States of America and therefore deserving of its privileges and protections.

![]()

Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, Professor Emeritus, Department of Political Science, Wilfrid Laurier University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

"Voices of the RSC” is a series of written interventions from Members of the Royal Society of Canada. The articles provide timely looks at matters of importance to Canadians, expressed by the emerging generation of Canada’s academic leadership. Opinions presented are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society of Canada.