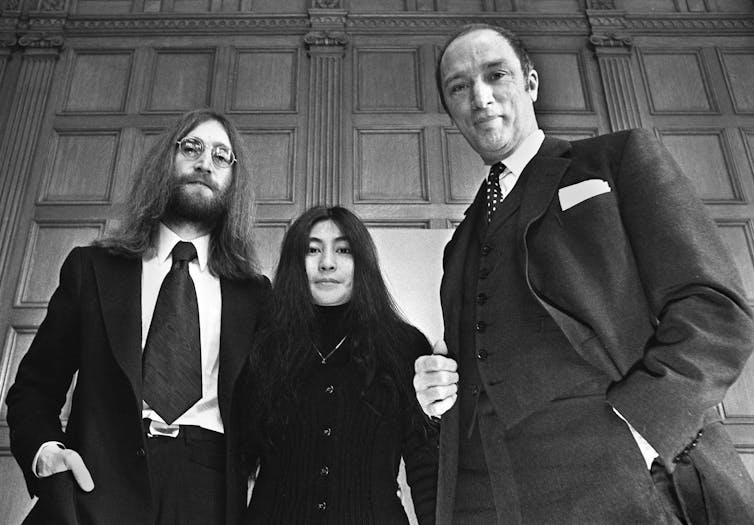

On Dec. 23, 1969, John Lennon and Yoko Ono went to Parliament Hill in Ottawa to meet Pierre Trudeau. The Canadian prime minister was the only world leader to meet with the peace activists. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Peter Bregg) Robert Morrison, Queen's University, Ontario

Fifty years ago this Christmas season, John Lennon and Yoko Ono came to Canada to launch one of the most unique and celebrated counter-cultural protests of the turbulent 1960s.

Lennon and Ono visited Canada several times in 1969, a year when the Vietnam War and the massive demonstrations against it reached new levels of intensity.

The famous Beatle and his new bride arrived in Toronto on Dec. 15, 1969, as part of the launch of their global “War is Over!” billboard campaign. A few days later, the couple sat down with Canadian media guru Marshall McLuhan to discuss the billboard initiative.

And on Dec. 23, Lennon and Ono achieved what seems to have been among their top priorities as the leading peace activists of the era: they met the prime minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau. According to the Beatles Bible website, it was the only time the couple was able to take their peace campaign directly to a world leader.

Canada was a favourite place for John and Yoko in 1969. During their first visit in the spring of that year, they staged their famous “Bed-In for Peace” at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montréal, lying down together for eight days in front of the world’s media to publicize their message of peace and, in the middle of it all, recording their anti-war anthem Give Peace a Chance.

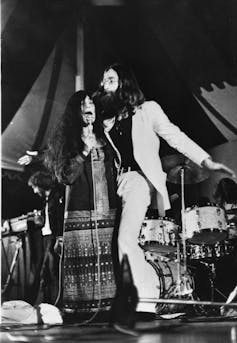

Recorded at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montréal: Dozens of journalists and celebrities attended, many of whom are mentioned in the lyrics. Lennon and Tommy Smothers on acoustic guitar.

Following Montréal, the couple travelled in June to the University of Ottawa, where student leader Allan Rock hosted them. Rock, Canada’s future United Nations ambassador, then took them in his car on a tour of the city, which included a stop at the prime minister’s official residence. Trudeau, they learned, was not in, but Lennon stood at the doorstep and wrote him a note before he returned to the car and they pulled away.

The second visit took place in September 1969 when Lennon, Ono and a hastily assembled version of the Plastic Ono Band (which for this gig included Eric Clapton) flew at the last minute from London to Toronto to take part in an all-day rock ‘n’ roll festival held at the city’s Varsity Stadium — and produced a live recording. Less than a month earlier, another rock ‘n’ roll festival — at Woodstock in upstate New York — had taken the American youth movement to its highest peak and given it a heady, almost fantastic, sense of its own power and purpose.

John Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono perform in their first public appearance as the Plastic Ono Band, at Toronto’s Varsity Stadium in September 1969. AP Photo

In their crusade for peace, Lennnon and Ono asked difficult questions, crucially relevant today.

How do we effectively protest against social injustices and war? It’s easy to deplore it. How do we all come together to stop it? Lennon and Ono did not, of course, put an end to violence. But they thought creatively and courageously about uniting people in opposition to it, and their example can inspire us today.

New hope for peace

In Europe, Lennon said: “We got a lot of hope from Woodstock.” If so many people could gather together for peace and not war, he said, perhaps counter-cultural forces could actually change the world for the better.

Their Toronto show was a fraction of the size of Woodstock, but Lennon was exhilarated by the experience. He closed his set with the song he most wanted the crowd to hear: Give Peace a Chance.

Almost three months to the day, Lennon and Ono returned to Canada, this time to announce a music festival to take place outside Toronto in the summer of 1970, billed to be far bigger than Woodstock.

The couple had renewed their efforts to meet Trudeau, and formal negotiations between their staff and Trudeau’s office were under way. Other world leaders — including British Prime Minister Harold Wilson and U.S. President Richard Nixon – did not want to know John Lennon. He was the dangerous Beatle, the “we are more popular than Jesus” Beatle.

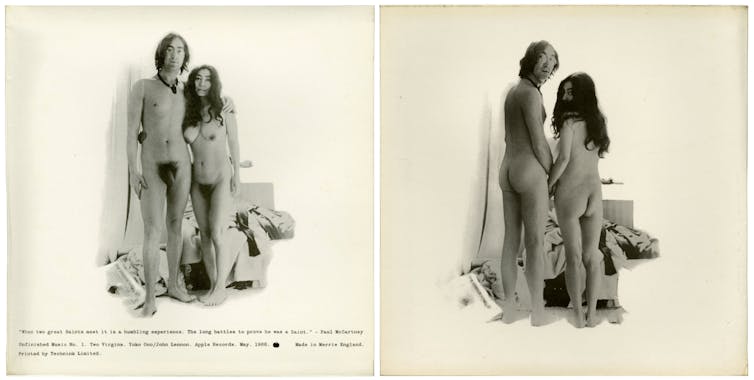

Just a year earlier, he had been convicted on drug possession charges and posed naked with Yoko on the jacket of their Two Virgins album. A month earlier, he had returned his MBE medal to the Queen in yet another snub to “The Establishment.”

John Lennon & Yoko Ono’s 1968 ‘Two Virgins’ LP Sleeve.

None of this stopped Trudeau from agreeing to meet him. From a political point of view, of course, Trudeau undoubtedly recognized that posing with one of the most famous rock stars in the world was an opportunity to boost his popularity among younger voters. But it’s also easy to imagine that Lennon’s iconoclasm appealed to Trudeau, and that he saw in Lennon an ally on issues such as effective peace activism and the escalating horrors of the Vietnam War.

A meeting of the minds

Lennon and Ono met Trudeau on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. After introductions and a brief photo session, they were ushered into Trudeau’s office. Lennon was nervous when the meeting began but, according to Ono, Trudeau immediately put him at his ease by telling him that he liked his book (presumably either In his Own Write from 1964 or A Spaniard in the Works from 1965).

John Lennon & Plastic Ono Band, Live at Toronto, Varsity Stadium, 1969.

Their primary topic of conversation was the Cold War. They agreed mutual trust had to be created so that “disarmament and peaceful diplomatic relations could begin.” Each of them — Trudeau and Lennon — would work “in very different ways toward this goal.” Although Trudeau was more than 20 years older than Lennon and the two men came from such very different worlds, it was a remarkable meeting of minds, personalities and agendas. The meeting was supposed to last 15 minutes. It lasted 50.

After Lennon and Ono left Trudeau, they met the media. “If all politicians were like Mr. Trudeau, there would be peace,” Lennon told them. Later, Trudeau remarked: “Give Peace a Chance has always seemed to me to be sensible advice.”

Nine days later, the 1960s were over and a new decade had begun. Lennon, back in London in January, wrote and recorded Instant Karma!, one of his greatest singles as a solo artist: “Why in the world are we here? / Surely not to live in pain and fear.” By the spring, however, plans for the massive peace concert outside Toronto had collapsed, and soon after Lennon’s life was overtaken by public disputes and personal demons.

Trudeau, meanwhile, entered his third year as prime minister in April, and by autumn, faced the biggest challenge of his political career with the FLQ crisis and the invoking of the War Measures Act. Within a year of their meeting, peace for both Lennon and Trudeau must have seemed further away than ever.

It’s easy to look back on Lennon’s activism and dismiss it as naive, as many did at the time and more have done since. That’s unfair. What Lennon was trying to do was to create hope.

Lennon looked squarely at the violence, misery and abuse that still thrives all around us. He responded with a model of peaceful protest, both on an individual level and in much larger ways, to activate the energies of resistance and to unite the popular with the political.

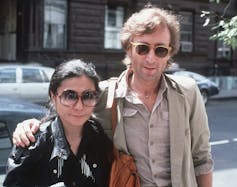

John Lennon, right, and his wife, Yoko Ono, at The Hit Factory, a recording studio in New York on Aug. 22, 1980, four months before the former Beatle was murdered. AP Photo/Steve Sands

Like Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., John Lennon was a peace activist who died at the hands of an assassin. Three years after Lennon’s death in 1980, Trudeau set out on the final major undertaking of his political career: his “peace initiative.” It was different from Lennon and Ono’s peace mission to Canada, yet it is possible to see in their crusade a precedent for Trudeau’s own initiative.

After visiting several countries on both sides of the Cold War divide, Trudeau brought his peace mission to a close with a speech to the Canadian House of Commons in February 1984. His initiative may not have accomplished all that he had wished. But as he recalled in his 1993 Memoirs: “Let it be said that we have lived up to our ideals; and that we have done what we could to lift the shadow of war.” In 1969, and especially in their three visits to Canada, Lennon and Ono, too, did what they could “to lift the shadow of war” and give peace a chance.

With violence raging and political movements of intolerance and isolation gaining so much ground today, we might draw inspiration from their words.

It’s now commonplace for pop icons and political leaders to meet and use their respective positions to champion progressive ideals. Half a century ago, when Trudeau opened his door to Lennon, that was not the case. Their extraordinary meeting marks the first time that a rock hero and a world leader met face to face to discuss the past, the present and the future. Their 50 minutes together highlighted the importance of peace to both men, as well as their shared commitment to raising political consciousness and mobilizing the popular forces of compassion and acceptance.

Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan interviews John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Toronto in December 1969.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]

![]()

Robert Morrison, British Academy Global Professor, Queen's University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

"Voices of the RSC” is a series of written interventions from Members of the Royal Society of Canada. The articles provide timely looks at matters of importance to Canadians, expressed by the emerging generation of Canada’s academic leadership. Opinions presented are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society of Canada.