African American Vernacular English is part and parcel of Black identity. Its distinctive linguistic features are denigrated — wrongly. (Shutterstock) Shana Poplack, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

After students at a California high school were recently told to “translate” Black English phrases into standard English, a community member at a school board hearing said: “The last thing they need — our children — is to be forced to attend class and to be mocked and bullied by students because of a lesson plan used to highlight African American Vernacular English.”

Few dialects of English have garnered so much negative attention. From the classroom to the courtroom, the place of African American Vernacular English is hotly debated. This is because people associate it with linguistic features now denounced as grammatically incorrect, like “double negatives” or verbs that don’t agree with their subjects. For example:

You might as well not tell them, ‘cause you ain’t getting no thanks for it. You might as well not tell them nothing about it, only just leave it in the hands of the Lord.

‘Cause I knows it and I sees it now.

Teachers and language mavens chalk these features up to “bad” English. Some linguists contend that they’re not English, but rather the legacy of an English-based Creole once widespread across British North America.

As a sociolinguist specializing in the structure of the spoken language, my team at the University of Ottawa Sociolinguistics Laboratory has been grappling with this issue for years.

Our research shows that many of these stereotypical non-standard features are direct offshoots of an older stage of English — that of the British who colonized the United States.

Tapping into early Black English

To understand how African American Vernacular English got the way it is now, you have to know what it was like before. But historical evidence of an earlier stage is in short supply: recording technology is too recent, and written representations are both scarce and unreliable. To access early Black English, we first had to reconstruct it from the speech of the African American diaspora.

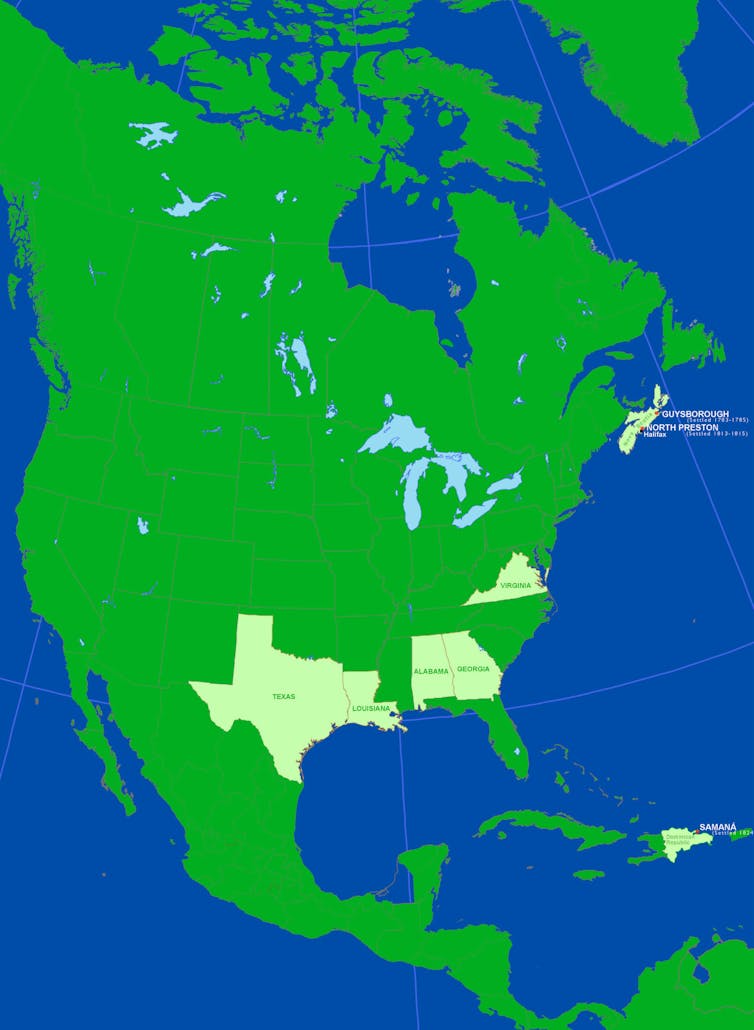

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, thousands of formerly enslaved African Americans settled in small enclaves in Africa, the Caribbean, South America and Canada, where their descendants still reside. Geographically and socially isolated, the key characteristic of linguistic enclaves is that they preserve older features.

Three such communities, never before studied in this connection, helped us shed light on the history of African American Vernacular English: Samaná, a small peninsula in the northeastern Dominican Republic, and North Preston and Guysborough in Nova Scotia. Thanks to local residents, we were able to locate and record the oldest members of these communities.

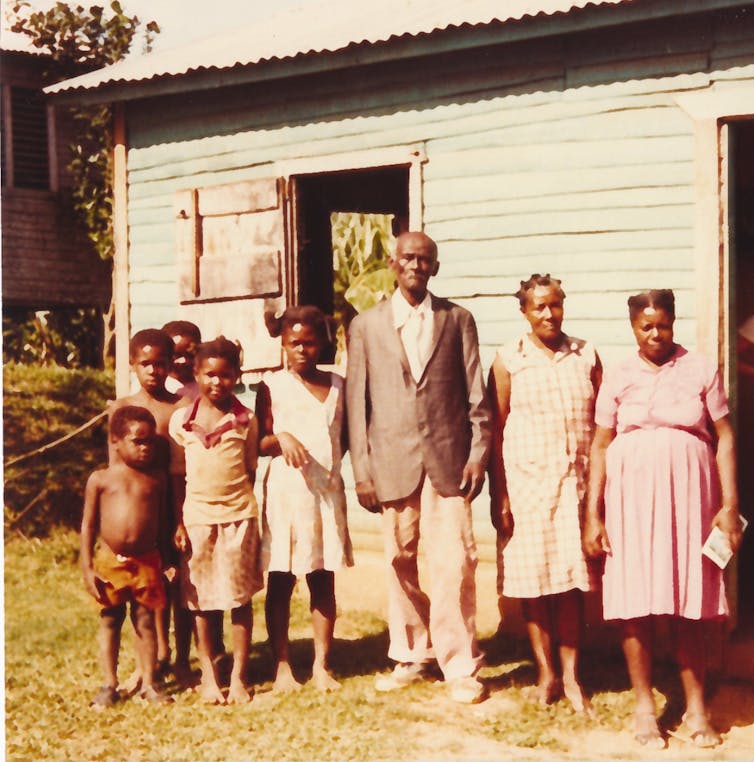

A Samaná family. (Shana Poplack, private collection)

Samaná, Dominican Republic

North Preston, Nova Scotia

Guysborough, Nova Scotia

We compared our recordings with others made nearly a century earlier with elderly African Americans born in slavery in the American South. These “Ex-Slave Recordings” allowed us to validate the diaspora materials as an earlier stage.

Ex-Slave Recordings

My team and I painstakingly analyzed these materials to detect statistically significant speech patterns, and compared them across different dialects of English. We also assembled nearly 100 grammars of English dating as far back as 1577. Such comparisons enable linguists to reconstruct linguistic ancestry; like evolutionary biologists, we seek shared retentions — features that have stayed the same despite changes elsewhere.

This revealed that many of the features stereotypically associated with contemporary African American Vernacular English have a robust precedent in the history of the English language.

Location of early Black English-speaking communities. (University of Ottawa Sociolinguistics Lab)

The “northern subject rule”

Consider the present tense. In standard English, only verbs in the third-person singular are inflected with –s, as in “he/she/it understands.” In African American Vernacular English, on the other hand, not only does the verb sometimes remain bare in the third person (e.g. “He understand what I say”), it may also feature –s in other persons, as in, “They always tries to be obedient.”

Our research on old grammars taught us that the standard English requirement that subject and verb agree in the third-person singular is actually relatively recent. As far back as 1788, the grammarian James Beattie noted that a singular verb sometimes followed a plural noun — exactly as we find in African American vernacular English today.

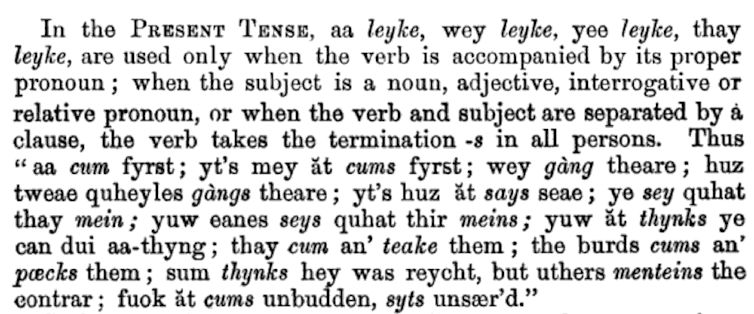

To our surprise, quantitative analysis of the way speakers used the present tense in our early Black English database showed that they follow a pattern described by the grammarian James Murray in 1873:

The northern subject rule. (Murray, J.A.H., 1873. The Dialect of the Southern Counties of Scotland: Its Pronunciation, Grammar, and Historical Relations. London: Philological Society.)

This pattern, known as the “northern subject rule,” involves leaving the verb bare when the subject is an adjacent pronoun (“They come and take them”) and inflecting it with –s otherwise (“The birds comes and pecks them”).

The problem with ignoring the past

Visiting americanos in Samaná. (Shana Poplack)

A linguistic pattern as detailed as the northern subject rule could not have been innovated by members of these far-flung communities independently. Rather, our comparisons confirmed that it was inherited from a common source: the English language first learned by enslaved individuals in the U.S. colonies.

In fact, the same pattern is heard in other varieties of English with no known African American input or ties, as in this example from Devon, in the United Kingdom:

You go off for the day, and gives ‘em fish and chips on the way home.

This is far from an isolated example. When we repeated this exercise, we found a historical precedent for many other linguistic features that are today considered grammatically incorrect.

Focusing on current differences between African American Vernacular English and standard English leads us down the garden path of concluding that it is “bad” English. But when we factor in history and science, we learn that it retained structures that standard English has now stamped out. Our results show that many salient features of African American Vernacular English were not innovated, but are instead the legacy of an older stage of English. African American Vernacular English should rightly be legitimized as a conservative and not incorrect variety of English, one whose core grammatical difference is its resistance to mainstream change.

Listen to the northern subject rule in action

They speak the same English. The English people talks with grammar.

That’s why, you know, they celebrate that day. Coloured folks celebrates that day.

Oh, I live my life. I and Emma, and Aunt Bridgie all — we all lives our life.

He know the first snowfall, he know the first guys that shoots the deer and everything.

All examples are reproduced verbatim, with permission, from original audio recordings housed at the University of Ottawa Sociolinguistics Laboratory.

![]()

Shana Poplack, Distinguished University Professor | Canada Research Chair in Linguistics | Founding Director of the Sociolinguistics Laboratory, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

"Voices of the RSC” is a series of written interventions from Members of the Royal Society of Canada. The articles provide timely looks at matters of importance to Canadians, expressed by the emerging generation of Canada’s academic leadership. Opinions presented are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society of Canada