Prenatal nutrition plays an important role in shaping the future health of an infant.

(Shutterstock)

Sandi Azab, McMaster University and Sonia Anand, McMaster University

What happens in the womb and during the first 1,000 days of life is critical to shaping a baby’s future health, a fact that is becoming ever more apparent as research dives deeper into this period.

A glaring example is gestational diabetes, a temporary form of diabetes that some women develop during pregnancy.

Though gestational diabetes usually disappears after delivery, its presence during pregnancy doubles — and in some cases triples — the risk of future Type 2 diabetes for both the mother and her child.

This problem deserves our attention, as do other factors in early childhood that also contribute to future risk of diabetes. These include low-quality diet, ultraprocessed foods and sedentary lifestyle due to heavy screen time, as well as pressures at work-life integration, which is challenging urbanized societies worldwide.

Gestational diabetes risks

A high-quality diet in pregnancy and healthy weight before pregnancy can reduce the risk of gestational diabetes and reduce the chance of transmitting this risk to one’s offspring.

(Shutterstock)

Sometimes the way to root out threats to the health of mothers and children is through large-scale research sampling the entire population. Sometimes we need to take a deeper look at specific communities to find issues that affect them more than others.

We know that in Canada, gestational diabetes occurs more commonly in racialized populations. South Asian, Middle Eastern, North African and East Asian women experience the condition more frequently than white women of European origin.

Our population health research among the South Asian population — the largest non-white ethnic group in Canada — provides some reason for hope. We know that a high-quality diet in pregnancy and healthy weight before pregnancy can reduce the risk of gestational diabetes and reduce the chance of transmitting this risk to one’s offspring.

This is one of many valuable findings we have made by studying 5,000 mother-baby pairs in birth cohort studies of different ethnicities, which together form the Canadian NutriGen consortium at the Chanchlani Research Centre (CRC) at McMaster University, where we work.

Birth cohort studies

Birth cohort studies look at groups of mothers and their babies from birth or even earlier and follow them for many years, gathering detailed measurements such as weight, blood pressure and diet as well as biological samples such as blood.

This type of research requires teams of experts from different fields, such as medicine, nutrition, statistics and biochemistry, to work together and look at results from different angles, as we do at the CRC.

Sometimes, it requires engaging with specific ethnic communities to build trust that enables such research. Sometimes it requires collaborating with researchers from different countries to expand our work to different settings and populations.

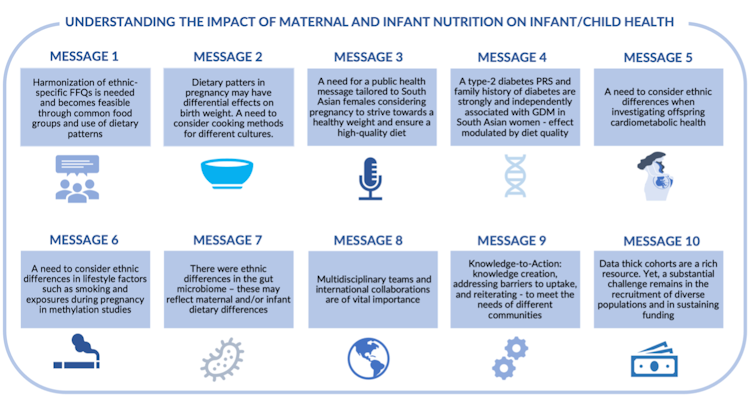

Ten key messages from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant ‘Understanding the impact of maternal and infant nutrition on infant/child health’

(Azab, Kandasamy, Wahi, Lamri, Desai, Williams, Zulyniak, de Souza, Anand), CC BY

To understand specifically how a mom’s diet affects her baby’s health, we need to consider her cultural background, which can determine what and how she eats.

We use ethnically tailored diet-measurement tools called food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) where moms recall their dietary intake over the past 12 months.

We focus on common food groups and dietary patterns that show overall eating trends and habits rather than occasional or standalone food items.

This approach considers the diversity of foods typically consumed within different ethnic populations.

We have grouped consumption into diet patterns such as plant-based, western and health-conscious categories that have revealed, for example, that a mother’s plant-based diet is protective against eczema in her baby for both South Asians and white Europeans and linked to birthweight in both groups.

Sharing research findings

In addition to the traditional research communication channels of publishing academic papers and participating in conferences, we share knowledge from birth cohort studies directly with affected communities and physicians.

Our team has created videos, for example, reflecting specific findings in the voices of participants such as the Six Nations Indigenous community in Ontario and the South Asian community.

We also developed SMART START,, an informational video and illustrated booklet to promote healthy living focused on diet and physical activity before and during pregnancy.

Sometimes our findings lead to more questions and more research, such as exploring what type of lifestyle changes can prevent gestational diabetes.

Our birth cohort studies show how research that includes both average- and high-risk populations can lead to insights that benefit all groups, and we can tailor our communications to reach communities more effectively.

We plan to extend our work to people of other ethnic origins heavily impacted by metabolic disorders, such as the East Asian, African and Middle Eastern communities, as well as expand our research in partnership with newcomer families and other underserved populations in our community, who face unique challenges such as fewer opportunities for physical activity or a healthy diet.

This kind of research opens doors to important discoveries in human development, and can identify biomarkers of health risks in specific populations. It is crucial to the health of all that we include diverse populations in such long-term projects in Canada.

![]()

Sandi Azab, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Global Health, McMaster University and Sonia Anand, Associate Vice-President Global Health, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.