COLUMBUS AND PANDEMIC CONTAGION: HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS TO COVID-19

COLUMBUS AND PANDEMIC CONTAGION: HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS TO COVID-19

W. George Lovell | December 9, 2020

W. George Lovell, FRSC, Professor of Geography at Queen's University and Visiting Professor in Latin American History at Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Seville, Spain.

A previous iteration of "Columbus and Pandemic Contagion" appeared in Queen's Quarterly, 127, 3 (Fall 2020).

On October 12, 1492, after thirty-three days at sea, Columbus saw fit to record his fateful landfall with hyperbolic verve. “Come and see the men who arrived from the sky!” he understood the inhabitants of Guanahaní, an island in the Bahamas, to declare. “Bring them food and drink!” The victuals furnished him form part of what Alfred W. Crosby (1972) famously coined the “Columbian Exchange,” transfers between the New World and the Old of plants, animals, goods, and commodities neither had known before, which proved of mutual benefit.

One transfer not so beneficial was epidemic disease, especially the impact of Old World maladies (smallpox was perhaps the worst scourge of many) on New World populations never before exposed to them, and so immunologically vulnerable. Because of this novelty of contact between autochthonous peoples and alien pathogens, a key determinant in the global scheme of empire, the arrival of Europeans on American shores may well have triggered the greatest destruction of human lives in history. Unforeseen outcomes centuries ago resonate with the ravages of COVID-19 today. What befell Indigenous peoples allows us to reflect on the catastrophic effects that contagion can have on susceptible and unsuspecting hosts in “virgin-soil” environments. Foremost in comprehending the scale and rapidity of post-contact decline are bouts of infection against which Amerindians were defenceless.

Are there any parallels between Old World intrusion in the late fifteenth century and pandemic eruption in the early twenty-first? Two come to mind. One is the velocity of infection: the speed with which COVID-19 spread from a metropolis in central China to remote corners of Amazonia is, quite literally, breathtaking. Columbus’s ships may not have been as fast a vector as jet planes, but they were conduits of contagion nonetheless. Furthermore, just as COVID-19 has afflicted some countries (or some areas within a country) more than others, so too half a millennium ago did disease operate with notable spatial variation and long-term demographic fluctuation, east to west, south to north across the hemisphere. The extinction of native communities in the Caribbean, for example, contrasts with over twenty distinct Maya groups to this day constituting roughly half of Guatemala’s national population. Better, then, to look at regional scenarios before engaging in hemispheric and global evaluation.

Hispaniola

No scenario provokes such controversy, nor such disagreement about the size of aboriginal numbers at contact, as Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Its Arawak or Taino inhabitants were the first “Indians” not only to be so labelled but also the first whose island home was invaded and destroyed – and they along with it, as was the case in Canada with the Beothuk of Newfoundland.

The range of contact estimates for Hispaniola is staggering, from a mere 60,000 to a massive 8 million, with myriad tallies in between. Whatever figure is conjured up, however, is but a prelude to erasure: by 1519, barely a quarter-century after Columbus came ashore, Hispaniola and its Antillean neighbours had been gutted to what geographer Carl O. Sauer (1996, 204) described as “a sorry shell.” What could have caused such calamitous, irreversible depopulation?

Smallpox. Scrutiny by historians Juan Gil and Consuelo Varela (1997) of a hitherto unknown report of Columbus establishes the presence of “viruelas,” the Spanish word for smallpox, which they date as having arrived in Hispaniola in the wake of the admiral’s second voyage of 1493. After the devastation of smallpox, Spaniards wanted little more to do with where it had wrought such ruin. Riches beckoned on the mainland to the west, toward which sailed an armada led by the conquistador Hernán Cortés.

Mexico

Spaniards under the command of Cortés landed on the Mexican coast at Veracruz on Good Friday, 1519. They soon realized that they had entered a populous realm, organized, settled, and cared for very differently from the Caribbean islands they had been so desperate to leave. The splendours of Mesoamerica were many, but none more spectacular than the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán. There Cortés, like Columbus in the Bahamas, was welcomed hospitably. After his intent to seize power became apparent, he and his men were driven out, fortunate not to be killed in an Aztec uprising. They sought safe haven in nearby Tlaxcala, whose people sided with the Spaniards against the Aztecs, their hated enemies.

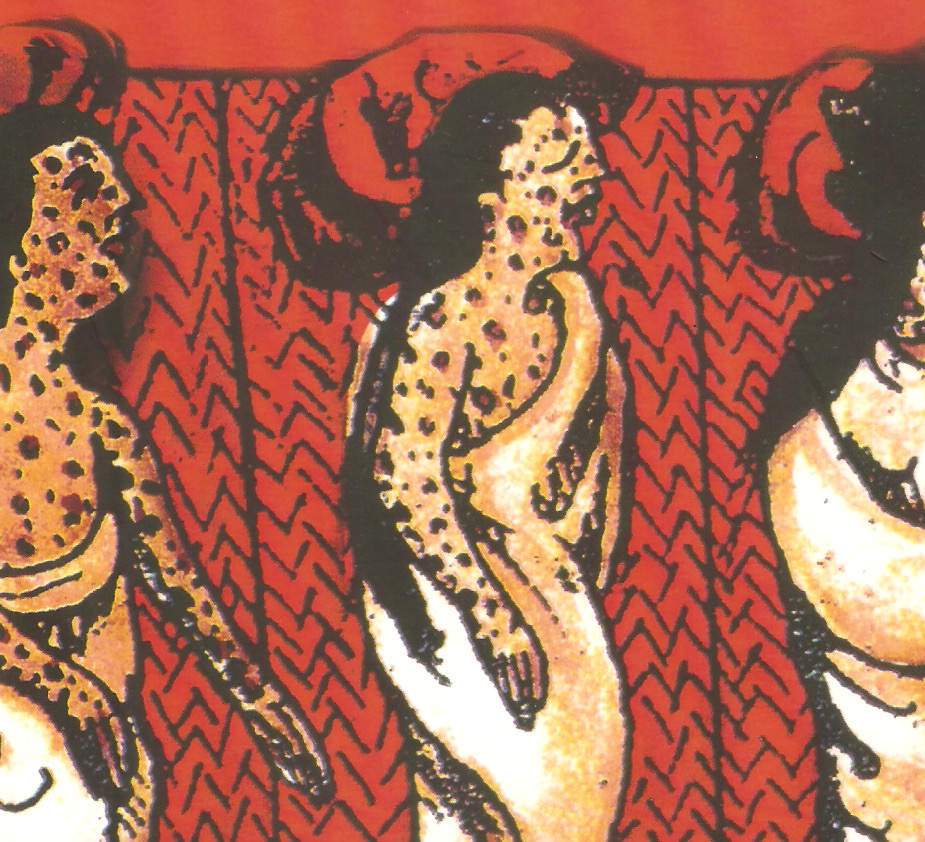

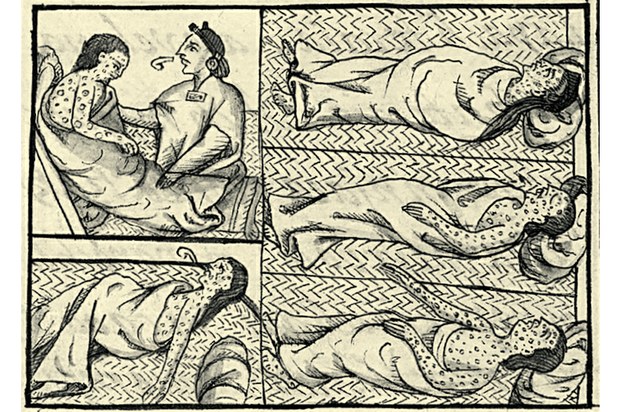

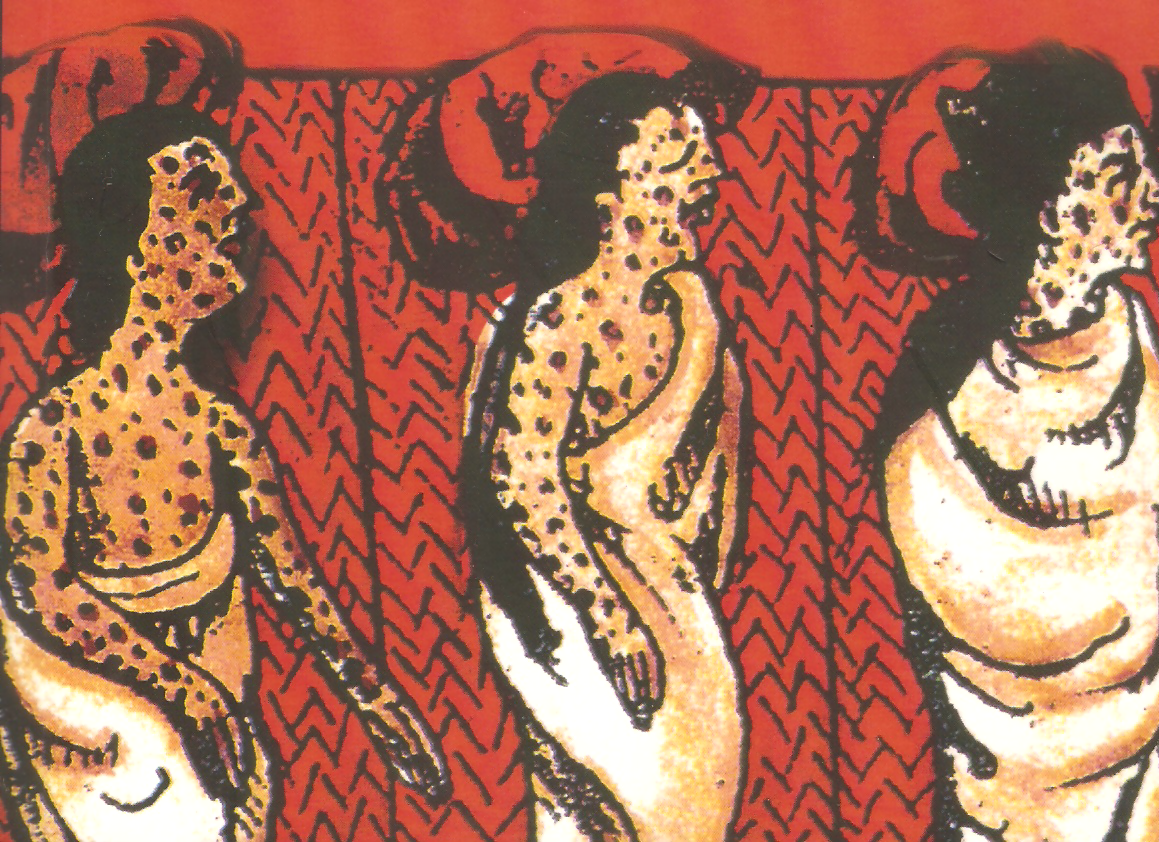

A year or so lapsed before a Tlaxcalan-Spanish alliance forced the surrender of Tenochtitlán. Its fall on August 13, 1521, came about primarily because of the turmoil unleashed by another outbreak of smallpox. Because the Aztecs, in the Mesoamerican tradition, had inherited a sophisticated system of writing, we have their testimony to draw on, one text running:

About the time that the Spaniards had fled, there came a great sickness, a pestilence, the smallpox. It spread over the people with great destruction, causing great misery. Some people it covered with pustules, everywhere, the face, the head, the breast. Many indeed perished from it. They could not walk; they could only lie at home in their beds, unable to move, to raise themselves, to stretch out on their sides, or lie face down, or upon their backs. If they stirred they cried out with great pain. Like a covering over them were the pustules. Indeed many died of them. But many just died of hunger. There were so many deaths that there was often no one to care for the sick; they could not be attended to.

How many may have perished, in Tenochtitlán and the rest of central Mexico, depends on how many we think were alive to begin with. As with Hispaniola, the range of contact-period estimates is dizzying, from a low of 4.5 million to a high of 25.2 million. Whatever count is accepted, and scholarly opinion now favours sizable numbers, outbreaks of Old World disease in the century after Spanish intrusion are again the most plausible cause of Indigenous depopulation, calculated by historical demographers Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah (1979, 102) at a horrendous 97 percent.

After reaching a nadir of 730,000 in the years between 1620 and 1625, native Mexicans began to adjust to European and African presence by generating immunities to Old World infections, which allowed them – unlike their less numerous and less developed counterparts in Hispaniola and elsewhere – to recover slowly from the epidemiological impact of conquest. Of Mexico’s present population of 129 million, some 15 percent are considered Indigenous.

Guatemala

Estimates of contact numbers in Guatemala vary from a low of 300,000 to a high of 2 million. Post-contact demise conforms to the trajectory for central Mexico: collapse between 1519 and 1624-28 followed by intermittent recovery and eventual increase, contact numbers reached again quarter-way through the twentieth century. Today in Latin America, Guatemala is second only to Bolivia in the percentage of its national population registered as Indigenous.

Native deaths between contact and nadir, a precipitous 93.4 percent, can be correlated with no fewer than eight pandemics (Lovell [1992] 2001; Lovell and Lutz 2013, 251). Waves of sickness, aptly dubbed “the shock troops of the conquest” by Murdo J. MacLeod (1973, 40), arrived in Guatemala five years before the Spaniards themselves did. In most instances it is difficult to determine what the illness actually was, because ambiguous, contradictory, or inadequate descriptions defy accurate diagnosis. Such is the case with the first pandemic, a disease registered in an Indigenous account – like the Aztecs, Mayas knew how to write and so recorded their own history – as follows:

When the pestilence began, oh my children, first there was a cough, then the blood was corrupted, and the urine became yellow. The number of deaths at this time was truly terrible. We were plunged in great darkness and great grief, our fathers and forebears having contracted the plague, oh my children.

Truly the number of deaths among the people was terrible, nor did the people escape from the pestilence.

The ancients and the fathers died alike, and the stench was such that men died of it alone. Then perished our fathers and ancestors. Half the people threw themselves into the ravines, and the dogs and foxes lived on the bodies of the men. Fear of death destroyed the old people, and the eldest son of the king at the same time as his brother. Thus did we become, oh my children, and thus did we survive – we were all that remained.

The advance guard that cut down Maya peoples in Guatemala had a similar role to play in the campaign launched by Francisco Pizarro to conquer the Inca Empire.

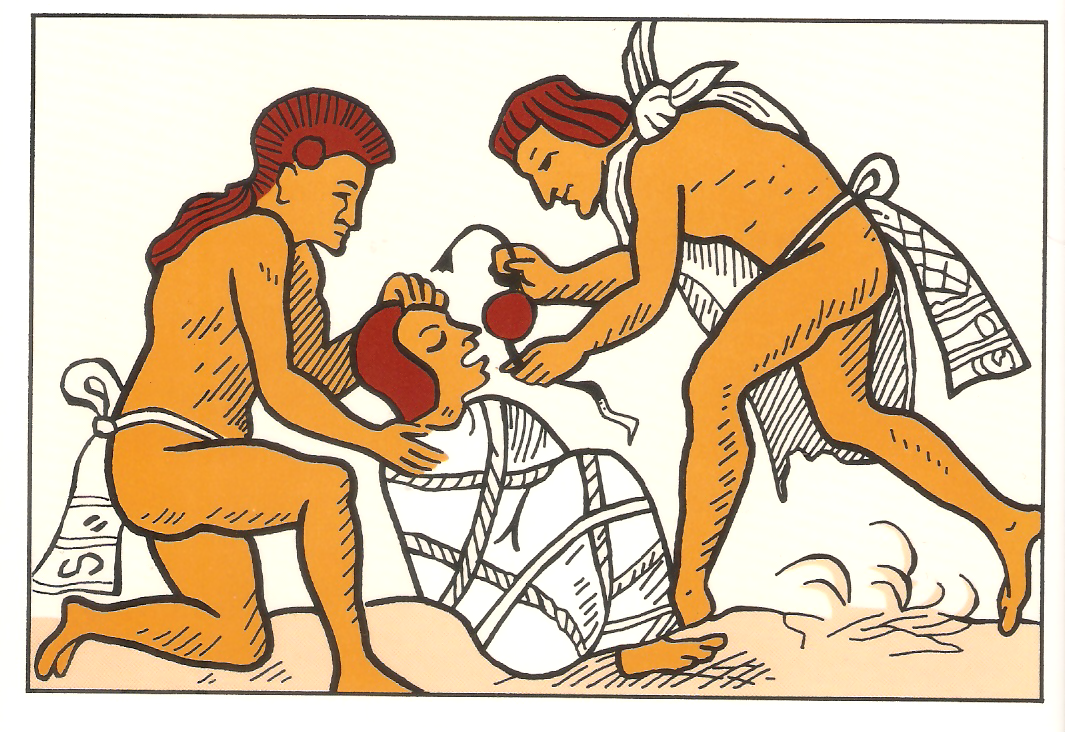

Ecuador and Peru

As in Central America, contagion preceded the actual arrival of Spaniards in the Andes by several years, diffusing ahead of them to weaken native resistance. An outbreak of what may have been hemorrhagic smallpox, whereby a strain of the virus infects the blood, causing a skin rash similar to that produced by measles, entered the Ecuadorian Andes in 1524. There it resulted in considerable loss of life. Among its victims was the Inca ruler Huayna Capac and his designated heir, Ninan Cuyuchi. Their deaths ignited a divisive civil war between two of the Inca’s sons, the half-brothers Atahualpa and Huascar, rival contenders for their father’s throne By the time Pizarro followed up his coastal reconnaissance of the 1520s with an inland campaign in the 1530s, the chaos caused by severe sickness facilitated Spanish victory. Like Aztec Tenochtitlán, the Inca capital Cuzco was taken as much by contagion as by the might of Pizarro.

Linda A. Newson ([1992] 2001) records eighteen epidemics in Ecuador alone between 1531-1533 and 1618. She estimates the contact population to have been 1.6 million, about half of whom lived in the sierra region, one-third on the coast, and the remainder (15 percent) in the Amazonian lowlands east of the Andes. The native population of the sierra dropped from 838,600 to 164,529 during the sixteenth century, a fall of 80.4 percent. Newson (1995) computes a decline of 95.3 percent for the coast, from between 546,828 and 571,828 to 26,491. As with the etiology of COVID-19, her findings stress regional differences as well as variations within a region, reflecting cultural and environmental conditions that are area-specific or place-specific, factors not taken into suficient consideration before.

A figure of 9 million for Peru on the eve of conquest straddles a range of estimates from 4 million to 15 million (Cook 1981). A century later, following more than twenty epidemic outbreaks, the heirs of the Incas are thought to have numbered around 600,000.

Brazil

Pedro Álvares Cabral is the Portuguese equivalent of Columbus. Allegedly, the fleet he captained was blown off course as it sailed from Lisbon to round the Cape of Good Hope, at the southern tip of Africa, en route to India. Landfall on the coast of Brazil on April 22, 1500, inadvertent or otherwise, thereafter meant that Portugal would penetrate South America from an Atlantic seaboard while Spain moved into the heart of the continent from the opposite direction, that of the Pacific. The two imperial powers disputed territorial ownership even before either had any sense of the enormity of the Amazon interior, which the Portuguese laid claim to in forays from the east despite a Spaniard, Francisco de Orellana, being the first to navigate the mighty river downstream from the west in 1542.

Prior to European intrusion, as many as 8 to 10 million people may have inhabited Greater Amazonia (Denevan 2014) . The nature of Indigenous societies and their response to foreign sorties was a decisive factor in determining survival. Sedentary populations under Spanish domination adapted to the advent of strangers through epidemics that accompanied or arrived ahead of them becoming endemic, meaning that introduced infections (smallpox, measles, mumps, typhus, influenza, and whooping cough, to name but six) over time became part of the Amerindian disease pool, affording the advantages of herd immunity. This was not the case in Portuguese domains, where less sedentary groups fled assault and enslavement for the refuge of the forest. There, in distant reaches of what would eventually be Brazil, native communities were sheltered from sickness until the frontier of European expansion caught up with them. In 2020, the remaining relatives of entire peoples wiped out in the sixteenth through twentieth centuries – fewer than 1 million of Brazil’s population of 210 million are Indigenous, 0.4 percent of the national total – are faced with the same threat from COVID-19 as their ancestors were by other maladies in 1500.

Hemispheric and Global Perspectives

Hemispheric estimates of Amerindian numbers at European contact are as disparate as the regional components alluded to above. Borah (1976) championed upward of 100 million, an estimate that echoes the 90 million to 113 million of Henry F. Dobyns (1966). Both are in stark contrast to the 8.4 million of Alfred L. Kroeber (1939), the 13.4 million of Ángel Rosenblat (1954), and the 15.5 million of Julian H. Steward (1949). Perhaps the most judicious assessment to date has been made by William M. Denevan ([1976] 1992), who considers 54 million conservative. Modelling of extant data (Koch et. al 2019) has generated an estimate of 60.5 million, mid-way between a range of 44.8 million to 78.2 million

How many Native Americans died in the pandemic aftermath of Columbus remains elusive, but fatalities in excess of 50 million – the “Great Dying” invoked by Alexander Koch (2019) and his associates – cannot be ruled out. In terms of historical comparison, the Black Death (bubonic plague) that haunted Europe between 1346 and 1353 is reckoned to have killed an estimated 50 million (Benedictow 2004), the Spanish Flu between August 1918 and March 1919 globally over 25 million (Crosby 1989). World War I claimed an estimated 40 million lives, World War II an estimated 60 million (Internet Archive n.d.)

Having deluded ourselves for so long that Homo sapiens controls all, we are paying a high price for being caught off guard when COVID-19 first struck and thereafter exacted such a heavy toll. Government unpreparedness and tardy response in combatting the virus are matched by lack of awareness among populations at large of the role disease has played in shaping past events and predicaments – in the Americas above all. It is not easy to discern why this is the case. Prominent public intellectuals, the likes of Michael Bliss, Wade Davis, Naomi Klein, and Margaret MacMillan, have played their part historicizing the present as they engage a general readership and raise its consciousness accordingly; in particular, the connection between Old World disease and New World depopulation has been addressed by Ronald Wright in his bestselling Stolen Continents ([1992] 2003) and popular What Is America? (2008) and by Charles C. Mann in his acclaimed 1491 (2005) and 1493 (2011). Perhaps COVID-19 will prove to be an unwelcome but pertinent corrective.

Meanwhile, Latin America has been especially hard hit by the virus’s lethal rampage. Cumulative deaths in the region have surged past even those of the United States, with Brazil and Mexico the worst affected. Despite alarming rates of infection, however, medical advances and humanitarian initiatives make it unlikely that mortality from COVID-19 will approximate the Amerindian holocaust of five centuries ago – unlikely, but cause for concern and prevention nonetheless.

Columbus, like so many of his ilk, may now be toppled from grace, but his legacy lingers.

References

Anderson, Arthur J. O. and Charles E. Dibble., trans. 1978. The War of Conquest: How It Was Waged Here in Mexico. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Benedictow, Ole J. 2004. The Black Death, 1346-1353: The Complete History. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press.

Borah, Woodrow. 1976. “Renaissance Europe and the Population of America.” Revista de Historia 105: 47-61.

Brinton, Daniel G. 1885, ed. and trans. The Annals of the Cakchiquels. Library of Aboriginal American Literature 6. Philadelphia.

Cook, Noble David. 1981. Demographic Collapse: Indian Peru, 1520-1620. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cook, Sherburne F. and Woodrow Borah. 1979. Essays in Population History. Vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Crosby, Alfred W. 1989. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Infuenza of 1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crosby, Alfred W. 1972. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Denevan, William M., ed. [1976] 1992. The Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Denevan, William M. 2014 “Estimating Amazonian Indian Numbers in 1492”, Journal of Latin American Geography, 13, 2: 207-221.

Dobyns, Henry F. 1966. “Estimating Aboriginal American Populations: An Appraisal of Techniques with a New Hemispheric Estimate.” Current Anthropology 7: 395-449.

Galeano, Eduardo. 1985. Memory of Fire I: Genesis. Translated by Cedric Belfrage. New York: Pantheon Books.

Gil, Juan and Consuelo Varela, eds. 1997. Cristóbal Colón: Textos y documentos completos. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Internet Archive. (n.d.). https://archive.org/.

Koch, Alexander, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, and Simon L. Lewis. 2019. “Earth System Impacts of the European Arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492.” Quaternary Science Reviews 207: 13-36.

Kroeber, Alfred L. 1939. Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 38. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lovell, W. George. [1992] 2001. “Disease and Depopulation in Early Colonial Guatemala,” pp. 49-83 in “Secret Judgments of God”: Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America, edited by Noble David Cook and W. George Lovell. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Lovell, W. George and Christopher H. Lutz, with Wendy Kramer and William R. Swezey. 2013. “Strange Lands and Different Peoples”: Spaniards and Indians in Colonial Guatemala. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

MacLeod, Murdo J. 1973. Spanish Central America : A Socioeconomic History, 1520-1720. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mann, Charles C. 2005. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Mann, Charles C. 2011. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Newson, Linda A. [1992] 2001. “Old World Epidemics in Early Colonial Ecuador.” Pp. 84-112 in “Secret Judgments of God”: Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America, edited by Noble David Cook and W. George Lovell. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Newson, Linda A. 1995. Life and Death in Early Colonial Ecuador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Rosenblat, Ángel. 1954. La población indígena y el mestizaje en América. 2 vols. Buenos Aires: Editorial Nova.

Sauer, Carl O. 1966. The Early Spanish Main. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Steward, Julian H. 1949. “The Native Population of South America.” In Handbook of South American Indians, vol. 5: 655-68. Washington: Bureau of Indian Ethnology.

Wright, Ronald. [1992] 2003. Stolen Continents: Conquest and Resistance in the Americas. Toronto: Penguin Canada.

Wright, Ronald. 2008. What is America? A Short History of the New World Order. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press.