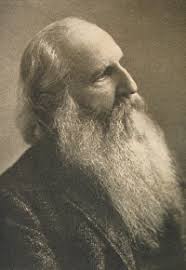

Maurice Bucke, physician, asylum superintendent and philosopher, is the third subject of this series on the Royal Society of Canada’s founding members. He is an old acquaintance, since my Master’s thesis was a study of the London, Ontario Asylum for the Insane when he was in charge of it. I wouldn’t call him an old friend, because of some of the misguided, indeed horrifying practices he performed at the institution, but he was certainly a picturesque figure. Let’s just say it’s best not to get too nostalgic about life before informed consent.

Bucke was born in England and received his medical training at McGill Medical School. He practiced medicine in the town of Sarnia in southwestern Ontario, and married a local woman, Jesse Gurd, with whom he had eight children. Through his contacts with the Provincial Secretary, he was appointed the superintendent of the London Asylum in 1877, a position he would maintain until his death. His only experience with the insane had been a year as superintendent of the Hamilton Asylum, but psychiatry was a newly emerging specialty with freedom to innovate. He did have a good reputation among local physicians. In 1886, he was approached to be Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University), but was unable to accept it while an employee of the province of Ontario.

Maurice Bucke was a unique individual. As a young man, he had struck out to California to find silver, and lost several of his toes to frostbite. He would walk with a limp thereafter. In his youth, after an evening of reading the works of Walt Whitman and Romantic poets, he had a mystical experience, which he would later term cosmic consciousness, and would some twenty years later write the book Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind. The book became influential in spiritual circles and was cited by Aldous Huxley and William James, among others. In Cosmic Consciousness, Bucke opined that there were three levels of human awareness: the highest level had been experienced by prophets like Jesus, Buddha, Moses and Walt Whitman; the second by those who had had mystical experiences, like himself; and the rest of the unenlightened masses.

Unlike other men of science, Bucke was a pioneer fan-boy. In one of his trips to the United States, he met the good gray poet, Walt Whitman, whom he associated with his mystical experience. He became enamoured with the writer and his seminal work, Leaves of Grass, and invited him back to London, where Whitman’s sensual musings on transcendentalism, nature and the soul caused quite a stir in conservative Ontario. But mostly a stir in Maurice Bucke, who grew a straggly beard and wore baggy pants and a floppy hat like his hero, whom he termed an “average man magnified to the dimensions of a God.” Bucke also would write Whitman’s biography (with much subject participation) and be his literary executor.

But first he had business at the asylum. The nineteenth century asylum was primarily a custodial institution, but by the 1880s, there were innovations such as the lessening of reliance on liquor, and on devices such as crib beds and restraint chairs. Bucke followed this model, and added patient labour routines (outside work for the men, inside housework for the women) to redirect patient energies into useful employment. He added massage to invigorate wasted muscles, and sports for the male patients.

Like many asylum superintendents, as well as directors of other total institutions, Bucke began to view the patient population as a research laboratory with both living and dead subjects. He set up a pathology lab to examine patient cadavers to determine what physical causes there could be of mental disorders. He then began speculating on causation of mental disorders, absorbing the contemporary paradigm of nerve theories in the age of electricity. He focused upon the “great sympathetic nervous system,” which included the reproductive organs, and cited the ovaries and the uterus as particularly problematic loci of mental disorders. He also linked sexual excess in men, particularly masturbation, as a threat to the male nervous systems by diminishing life force. Unlike other theorists on the supposed increase in nervous exhaustion among the middle classes in the bustling modern cities, Bucke had the research material at the ready to test his ideas. Unlike other Canadian asylum superintendents who also were confronted with recalcitrant and incurable patients, Bucke proceeded to do so. First he placed wire around the penises of fifteen patients to prevent them from practicing the habit, with the goal of curing their insanity, but this experiment was a failure.

Then he engaged in further actions which gave him, in the judgment of history, more infamy than fame. He performed over 200 gynaecological operations on patients over a six-year period, until ordered to stop by the Provincial Secretary. Bucke was hoping to make his name by proving his theory of the relationship between the great sympathetic nervous system and female insanity on the bodies of some of the most vulnerable members of any society, women committed to an asylum.

Mental illness, its causes and especially its cures, was a great mystery, and to some extent remains so today. Many asylum superintendents, neurologists and psychiatrists tried treatments such as insulin shock therapies, lobotomies, and electro-convulsive therapies with some limited successes. Nor was Richard Maurice Bucke the last Canadian researcher to attempt to find the Big Cure through the exploitation of the less powerful. Ewan Cameron’s infamous CIA-funded brain-washing experiments at the Allen Memorial Institute in Montreal in the 1950s and 1960s comes to mind. Bucke would have served the world better by putting down the scalpel, and re-reading Leaves of Grass.

Cheryl Krasnick Warsh

Vancouver Island University

"Voices of the RSC” is a series of written interventions from Members of the Royal Society of Canada. The articles provide timely looks at matters of importance to Canadians, expressed by the emerging generation of Canada’s academic leadership. Opinions presented are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society of Canada.