Advertising encourages consumption, including products and activities that use large volumes of fossil fuels. (Shutterstock)

Peter Dietsch, University of Victoria

There is no reasonable disagreement that humanity needs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. People might argue over how large a reduction is necessary or about the best ways to achieve it, but almost everyone agrees it has to be done.

The available science suggests that technological fixes alone will not do the trick. We need to reduce the consumption of high-emission goods and services, those made from fossil fuels or that rely heavily on them.

And yet, advertising for such goods and services is everywhere, encouraging fossil-fuel consumption: flights to Rome, pickup trucks and SUVs, cruises to Alaska, steak from Argentina and so on.

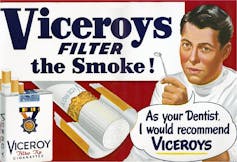

Should such advertising for fossil-fuel-intensive goods and services be prohibited? This would only be consistent with how we deal with other products whose consumption causes serious harm, such as tobacco. For example, the United Kingdom banned TV advertising of cigarettes in 1965, the United States banned cigarette ads on TV and radio in 1970, and Canada has banned all forms of tobacco advertising since 1989.

The harm principle

A core principle of liberalism holds that individuals should not be constrained in their actions, unless these actions cause harm to others. For instance, you are not allowed to drive through a residential neighbourhood at 100 kilometres per hour, because this would put the lives of others at risk.

Now, you might rightly point out that when you take a flight to a sunny beach in Mexico, you are not putting the lives of others at risk, at least not in the same, direct way. However, there is a collective action problem here: If everyone takes a flight to a sunny beach in Mexico, the aggregate emissions from all the flights will lead to a warmer planet, extreme weather events and will not only harm others but put lives at risk.

The emissions from cars, trucks and other gasoline-burning vehicles put lives at risk. (Shutterstock)

It is controversial whether this mediated harm from your flight to Mexico is enough to justify stopping you from going to Mexico. Instead, I propose to apply a weaker and less controversial version of the harm principle: When the actions of individuals cause significant harm to others, even indirectly and mediated through aggregate effects, then as a society we should abstain from encouraging these actions.

We know that the emissions from fossil-fuel intensive goods and services put lives at risk. We also know that, overall, advertising encourages their consumption. Therefore, on this version of the harm principle, we should ban advertising for fossil-fuel intensive activities.

An important precedent

As the World Health Organization points out, “tobacco kills nearly six million of its users each year.” Because of the harm smoking causes, its proven link to several forms of cancer in particular, states have taken measures to discourage it.

These measures include a comprehensive ban on all advertising for tobacco products under the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. They are further justified because of the second-hand effects of smoke, that is, the health risks for people other than the smoker themselves.

Tobacco kills nearly six million smokers annually. (clotho/flickr), CC BY-NC-SA

The number of people dying from climate change is already comparable to smoking-related deaths. One study estimates that between 2000 and 2019, more than five million people a year died due to the effects of climate change. With the frequency of heat waves, severe storms, floods and other extreme weather events set to increase due to climate change, this number will only grow in the coming years.

Given what societies have done on tobacco, it would only be consistent to ban advertising for fossil-fuel-intensive activities. In addition, the status quo is also inconsistent with the alleged commitment of governments to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Governments around the world have pledged to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, in an effort to meet the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5 C. Yet, they tolerate advertising for activities that are clearly counterproductive to achieving this ambitious goal. This is akin to a drug rehabilitation centre putting up posters everywhere telling its patients how great it feels to take drugs.

Where to start?

Coming up with a definition of a fossil-fuel intensive activity is a bit more complex than providing a definition of smoking, but it can be done. Here is a plausible starting point: Define a certain threshold of emission-intensity that qualifies the good or service for the ban.

For example, given that an average passenger vehicle emits about 2.3 grams of carbon dioxide per litre of gasoline, one might ban advertising for any vehicle that emits more than that, and subsequently lower the threshold to further encourage innovation. That same standard would then be applied to other means of transport such as flights, leisure boats, cruises. Similar thresholds for other categories of goods and services such as red meat or construction could also be defined.

Politically, the proposal faces two significant challenges: industry pushback and political reluctance to ask voters to rein in their lifestyle. Once again, valuable lessons can be learned from tobacco.

The trigger for change might lie in legal action that gives voice to the fundamental interests of members of future generations — those who are being harmed by fossil-fuel advertising today. We owe it to them not to encourage activities that will kill them.

Peter Dietsch, Professor, Philosophy, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

"Voices of the RSC” is a series of written interventions from Members and Officials of the Royal Society of Canada. The articles provide timely looks at matters of importance to Canadians, expressed by the emerging generation of Canada’s academic leadership. Opinions presented are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society of Canada.